Edwin Muir and the “Knox-ruined nation”

“For Scotland I sing, / the Knox-ruined nation”

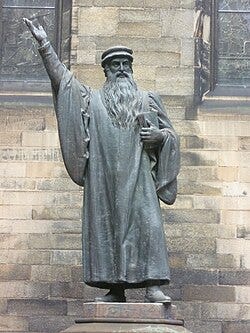

“For Scotland I sing, / the Knox-ruined nation”: these lines are part of “Prologue”, the first poem of George Mackay Brown’s debut collection. It is a sort of defiant poetic manifesto and here Brown allies the creative work of the artist with God’s holy men and women, the saints, in order to reconstruct Scotland, a nation “ruined” by the catastrophic legacy of sixteenth-century Calvinism preached by John Knox. He was a bit of bogeyman for Brown, a symbol for everything he hates. However, the idea of a harmonious Catholic society in medieval Scotland demolished by the Protestant Reformation does not originate with him, but is something he learned from the Orcadian fellow Edwin Muir, one of the most important Scottish writers of the twentieth century and the one who contributed most to the launch of Brown’s career as an author.

Muir and his poetic rival Hugh MacDiarmid were the high priests of the “Knox-ruined nation”, a proposition that recurs with surprising frequency in Scottish literature and criticism of the last century. Their thesis, shared by many authors of the “Scottish Renaissance”, was quite simple: if Scotland is now a gloomy country, marked by internal divisions and an embarrassing cultural backwardness, it is all the fault of the Calvinists, who are iconoclasts, quarrelsome and distrustful of the fallen, material world. In 1928, for example, MacDiarmid bitterly laments the “peculiar unfortunate form Reformation took in Scotland”, which was “anti-aesthetic to an appalling degree”, and was the root of “the general type of consciousness which exists in Scotland today – call it Calvinistic or what you want”. Muir’s view is even more despondent and it is described at length in his John Knox: Portrait of a Calvinist (Johnathan Cape, 1929), a book dedicated to MacDiarmid and destined to influence many Scottish intellectuals.

In a letter to his friend Sydney Schiff, Muir said of his biography of Knox that it was “more particularly written for the purpose of making some breach in the enormous reverence in which Knox has been held in Scotland, a reverence which I had to fight with too in my early years (so that I really feel quite strongly about it) and which has done and is doing a great deal of harm”. Moreover, in his book Muir writes that “the religion system of Calvin is one of the most extraordinary achievements of modern theology. It is in essence the work of one mind. It remained for almost three hundred years a complete and impregnable system, and to present day the edifice has never fallen: it has only been deserted, all but a forlorn handful of worshipers have vanished. During its age of power it formed the characters of great men, and changed the destinies of peoples” (including the Scottish one).

Muir’s John Knox, written in a captivating and witty style, is not a thorough historical study, but rather a psychological portrait of Knox that explores the evolution of his character and theology. The author himself declares this, writing that his biography is unlike any other, wishing to provide “a critical account of a representative Calvinist and Puritan.” This is both the book’s main flaw and its main merit: while it suffers from several inaccuracies and therefore lacks great historical value in itself, it is nevertheless highly interesting from a speculative point of view. In his work, in fact, Muir is particularly skilled at describing the corrupt spirit of the sixteenth century, in which Protestantism, in its various forms, spread due to the egocentricity of preachers who had no problem changing their ideas over time, according to convenience, and who willingly allied themselves with the same princes and nobles they had previously criticized in order to crush the poor people, when the latter seemed unwilling to embrace their new ideas. Emblematic of this attitude is Knox’s criticism of women, considering them the receptacle of all vices, only to later correct himself or moderate his tone when the Calvinist cause needed the support of Queen Elizabeth. Or, speaking of Knox again, his sometimes comical and wavering stance on the subject of the people’s loyalty to the sovereign is another topic on which his views changed depending on who sat on the throne.

The inevitable consequence is that in such a scenario, Catholicism retains a divine dimension that Protestants completely lack: the holy religion of the Church of Rome contrasts with a Protestantism that appears exclusively the work of human hands, the product of the egocentricity of self-styled prophets more interested in fame and personal success than the truth. And it is no coincidence that Protestants often found themselves at odds with each other, splintering their Churches into ever smaller groups. Knox also engaged in fierce debates with both the Anglicans and the Anabaptists, occasionally even distancing himself from the teachings of Calvin, his mentor.

It should also not be forgotten that in Scotland, as in other nations, the Protestant cause was fuelled by economic and political motivations that had nothing to do with religion. Among Knox’s supporters, for example, were double-dealing lords eager only to secure the wealth of the churches and abbeys that were meanwhile being destroyed, as well as nationalists who saw Calvinism primarily as a way to escape interference, first from the French and then from the English. Thus it happened that in Scotland, a religion supported by a minority was forcibly imposed. Muir writes:

“The Confession [of the Scottish Calvinism] had been drawn up in four days by a handful of barons and preachers; the punishments were intended to affect thousands of people who had never heard the new faith”.

And thirty-six years after the passing of this extraordinary Act four hundred parishes still had no ministers. In another passage, a few pages later, Muir analyzes Calvinist theology in more detail, focusing in particular on one of its central ideas – which the writer considers beastly – namely, that people are from the moment of their creation divided into the elect and the reprobate, with no possibility of changing their condition. He then moves on to examine its political and social application, and what Muir describes is something very similar to the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century:

“The virtues of that religion were its single-minded enthusiasm, and an intrepid spirit to which no task seemed impossible; its fault were a lack of understanding, an incapacity for human charity, and, above all, a consciously virtuous determination to compel and humiliate people for the greater glory of God. Its fundamental idea was the corruption of man’s nature, and its policy had necessarily, therefore, to be the policy of espionage and repression. Its sole instrument for keeping or reclaiming its members was punishment. The ministers had to correct their congregations; the elders had to correct the ministers; the congregations had to correct the elders. A Church such as this, held together by universal and reciprocal fault-finding, could not but have something ambiguous in its piety, and could not but encourage the self-opinionative and the censorious at the expanse of the sensitive and the charitable. It did more, however; it substituted for the particular tyranny of the priest a universal and inescapable public tyranny”.

This is why Geneva, the “city of God” desired by Calvin, for Muir is not too different from a hell on earth, whose flames are fuelled by a monstrous ideology.

And why did Knox, after forty years as a Catholic priest, decide to embrace Calvinism, becoming one of its most famous predictors? Compared to his contemporaries, Muir asserts, Knox was nothing extraordinary. He was neither original nor wise, nor did he possess great charisma. Indeed, he had repeatedly proven himself ambiguous, and his only true quality was an instinctive nature, typical of a man of action. The need to present himself as a prophet of God also reveals a probable inferiority complex, typical of those who fear comparison on equal terms (Mary of Guise and Mary Stuart, despite their errors, were two women far more gifted than he). And to such a man, Calvinist doctrine offered the certainty of never being wrong, which encouraged his natural obstinacy, and transformed his irrepressible desire to impose his will on others into a moral duty. Knox also had a irascible and violent nature, and the Old Testament, so dear to Calvinists, showed him that God was fundamentally like him and inclined to harshly punish every offense.

Muir’s final judgment on Knox and Calvinism is found in the final pages of his John Knox, where, in an appendix, he addresses the pernicious role Calvinism played in Scottish history:

“what Knox really did was to rob Scotland of all the benefits of the Renaissance. Scotland never enjoyed these as England did, and no doubt the lack of that immense advantage has had permanent effect. It can be felt, I imagine, even at the present day”.

By Luca Fumagalli