Hew Lorimer’s Quiet Catholic Scotland

Hew Lorimer in Scotland's Catholic arts movement.

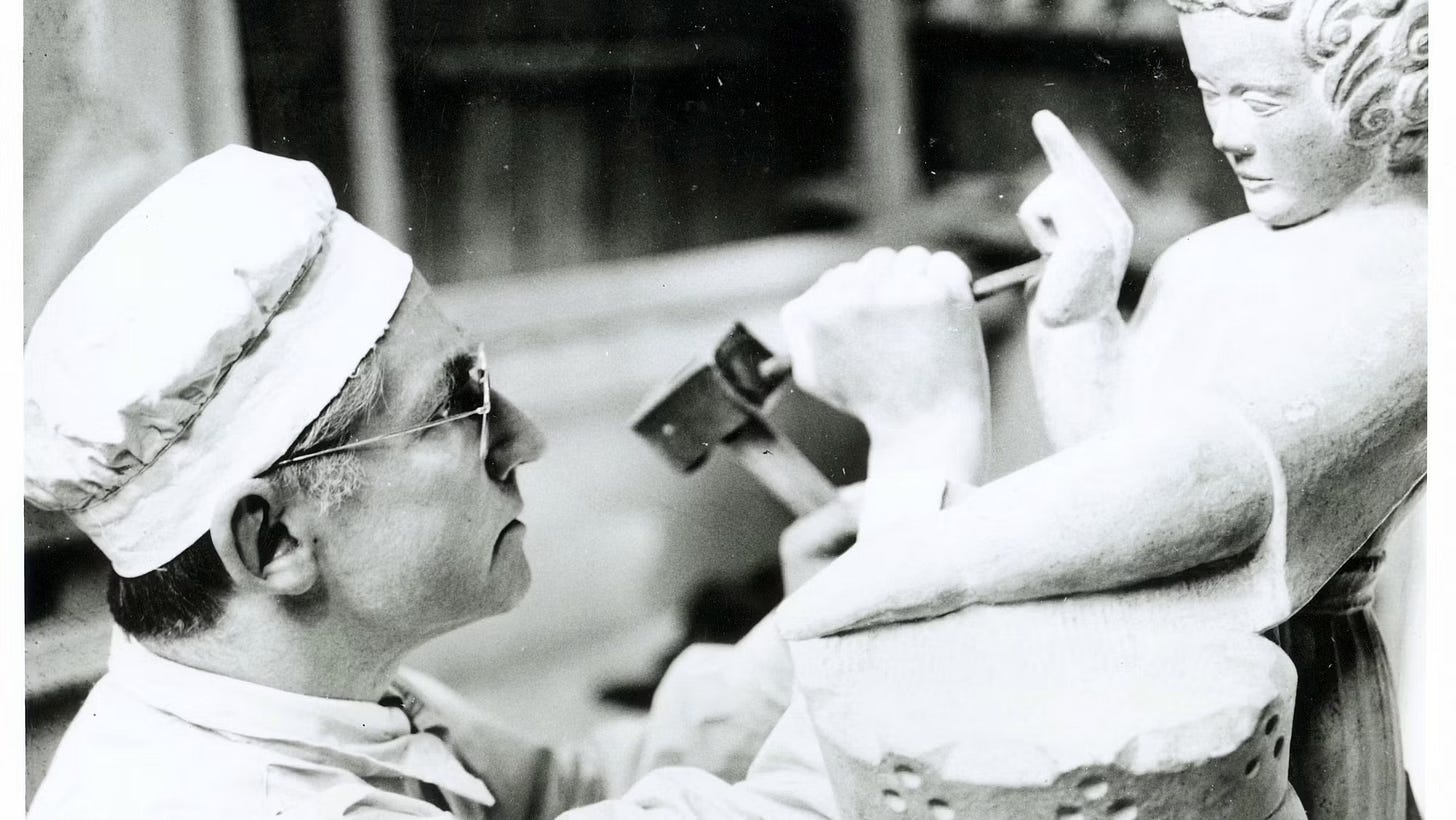

Fig. A

The fascinating history of Catholic artists of all disciplines in Scotland is very much a living history; a thread I shall follow in two parts. The recent sculptor in residence at Pluscarden Abbey, Philip Chatfield shares his artistic lineage through his mentor Jonah Jones with Scottish Sculptor Hew Lorimer, this is evident in their work with the clean lines and gold accents, reminiscent of the Celtic Revival style. Hew Lorimer converted to Catholicism in the 1930s after marrying his wife and was awarded the Papal knighthood (Order of St Gregory) as recognition for his work in sculpture for the Church near to the end of his life in 1993, and yet his work is not well known or even properly recorded. His work can however be viewed at his family home Kellie Castle in Pittenweem now in the hands of the National Trust for Scotland (for whom he was a representative), as well as on public buildings and in Churches around Scotland. Hew was born in Edinburgh in 1907 to renowned architect Robert Lorimer and Violet Wyld; he went on to study sculpture under Scottish architectural sculptor Alexander Carrick. Later on, Hew collaborated with many notable architects including Reginald Fairlie who belonged to a Scottish Catholic family and whose faith and love of Scottish heritage fuelled his work.

Like his father, Hew followed in the arts and crafts tradition of William Morris (although Scotland had it’s own vibrant Movement) and was concerned with his local community and regional traditions. The majority of his works can be seen around Fife, but also further North in Moray and South Uist. The humble settings for his craft, such as libraries, convents and power stations meant his work hardly gained the recognition of that which you’d find in a gallery and yet the diminishing care taken to build beautiful public buildings is keenly felt in our day, by those who notice such things. The Arts and Crafts Movement is centred on the pursuit of beauty in everyday life and therefore its accessibility for all, as architect James A Morris said:

“… there is a spiritual truth, a reach of soul as well as a reach of hand.”

He also spoke of how the artistic spirit flourishes within ‘rigorous tradition’ illustrated perfectly by our medieval Cathedrals.

There is certainly a Gospel message in the work of the Edinburgh Social Union’s Phoebe Anna Traquair’s breathtaking murals being for the eyes of patients and their families in the Chapel of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh. Traquair was part of a larger endeavour across Scotland to make public places beautiful and offer training in the arts to working class communities, Lorimer carried this torch into the 20th Century.

Similar to the work of Philip Chatfield at Pluscarden Abbey or any one of his memorials, looking at Lorimer’s work you’d perhaps be forgiven for thinking it had always been there; there is certainly a humility in the anonymity which compliments the spiritual element of the craftsmanship. Lorimer was heavily involved with conservation including the creation of several museums. In the 1950s, Lorimer was on the Trust Committee for The St Andrews Preservation Society which was concerned with preserving the traditional appearance of the town as well as The National Trust for Scotland’s Little Houses Scheme, Lorimer was particularly drawn to the coastal towns and their unique characters, colours and textures. Furthermore, when the Ministry of Defence proposed a missile testing range be constructed on South Uist, Canon John Morrison commissioned Lorimer to create the forty ton statue ‘Our Lady of the Isles’ as an act of resistance and to express the Island’s culture and way of life as well as perhaps as a physical petition for Our Lady’s intercession. The height and way in which Our Lady is guarding an infant Jesus seems to illustrate this story. There is a similar statue on the Isle of Barra, although the sculptor is unknown, perhaps another story of the quiet craftsman. Lorimer certainly had a penchant for the Scottish coastlines under Our Lady’s watchful eye, having assisted Reginald Fairlie in another project building Our Lady of the Sea in Tayport, Fife. Lorimer completed a very Celtic Holy Mother stood upright in a small rowing boat, holding the infant Jesus.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/63443245@N04/36483922964/

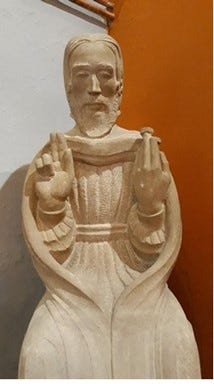

Another sculpture that stood out to me was the ‘Sacred Heart’ which was a gift to a school, however it has made its way to St John the Evangelist in Edinburgh. There is no obvious Sacred Heart image, instead Christ’s enfolding cloak is opened in the shape of a heart, where He is holding His crucifixion nails. This interpretation of the Sacred Heart illustrates the humility of Christ through it’s unfussy style and seated composition. Furthermore, it displays the ethos of the Arts and Crafts Movement in it’s quiet presence.

There is limited information on very simple local Church websites about these hidden gems, however I feel that paying attention to these details, appreciating the contributions of our Catholic artists in Scotland is a way that we can allow beauty to be our guide to truth.

https://www.stmarymagdalenes.co.uk

By Lucy Fraser

Fig A: Hew Lorimer at work, National Trust Archives

To see more of Lucy’s writing you can also find her on her own substack below: