St Baldred of the Bass

Part 1 and 2 of Reverend Stephen Holmes long read on St Balthere, or as he became known, St Baldred of the Bass.

This article, split into parts and slightly abridged, originated from the blog of Stephen Mark Holmes, Priest of the Scottish Episcopal Church (SEC) and Provost of St Ninian’s Cathedral in Perth. He was formerly Rector of the Church of the Holy Cross, Davidson’s Mains, Edinburgh. The blog is largely concerned with Christian liturgy, theology and history. You can find his blog here: Amalarius.

Part 1

For the past three years I have been learning about the saints who lived in my local area. It is a short walk from my front door in north-west Edinburgh to a place in the grounds of Lauriston Castle where I can look across the Firth of Forth to St Columba’s isle of Inchcolm, the ‘Iona of the East’. The island, with its twelfth-century Augustinian Abbey, is an ancient Christian site on the route from Iona to Lindisfarne. Nearby is Cramond Kirk, also dedicated to St Columba, which is on the site of an earlier church built in the praetorium of the Roman fort. Further down the Forth are the Bass Rock and the Isle of May, each with their own native saints. The Firth of Forth, with its islands and surrounding land, is a clearly defined area and has been studied from an environmental point of view in TC Smout and Mairi Stewart’s ‘The Firth of Forth: An Environmental History’ (Edinburgh, 2012). The Firth also has its own distinct spiritual ecology with a host of saints integrated in its landscape and seascape, including Adrian, Baldred, Cuthbert, Fillan, Margaret, Serf, and Triduana, as well as other saints who have become native such as Bride, Mary and Michael.

This series of posts aims to present the hermit Balthere or Baldred who lived on the Bass Rock. Some, remembering a popular TV series, may find his name funny. A genuine medieval Scottish knight called Sir Baldred Blackadder was almost certainly named after him. The aim, however, is less to amuse than to inform and to allow people to form a relationship with him. Balthere certainly existed and now lives with God, as someone wrote shortly after his death in 756, he ‘entered the way of the holy fathers by departing to him who had formed him in the image of his Son.’ May he pray for us and for the people of East Lothian.

Baldred is a local saint of the East Lothian coast whose memory has endured for well over a thousand years. He is said to have lived on the Bass Rock and three churches close to each other all claimed to have his body in the middle ages: Tyninghame, Auldhame and Preston (Prestonkirk, East Linton). There will be more on his multiple bodies later. All four places had churches dedicated to him and there was probably also a chapel of St Baldred at Tantallon Castle, by Auldhame and overlooking the Bass. Baldred has an enduring presence in the landscape along this stretch of coast in rock and water. On the map of this area we find rock features such as Baldred’s cradle, Baldred’s boat, and St Baldred’s cave. There are also two wells named after St Baldred at Auldhame and Prestonkirk (pictured below) and local histories mention St Baldred’s Whirl, an eddy or pool in the local river Tyne at Prestonkirk.

His presence lived on in the locality after the Protestant Reformation which attacked the memory and cult of the saints. A statue of St Baldred remained at Prestonkirk until 1770 when it was smashed, in 1824 James Miller of Haddington published a poem ‘St Baldred of the Bass: a Pictish Legend’, and in 1862 the Episcopalians of North Berwick opened a new church dedicated to St Baldred, which now has a statue of St Baldred and a stained glass window dedicated to him. Local Presbyterians have also installed stained glass windows of Baldred at St Andrew, Blackadder in North Berwick (1935) and Prestonkirk (1959). Roads are named after him in North Berwick and there is also a St Baldred’s Cottage at Tyninghame. Through the centuries down to today Baldred has not been forgotten in his locality.

Baldred is thus clearly a local saint. With a few significant exceptions, his cult seems not to have spread much beyond this closely bounded part of East Lothian but it remained alive. A Mass of St Baldred for his feast on 6th March is found in a fragment of a fifteenth century missal from Haddington, the local market town, used in binding the post-Reformation burgh court books. Baldred’s cult was, though, so local that it seems not even to have spread south when his Tyninghame body was removed to Durham Cathedral in the early 11th century by Elfred son of Westhou, sacristan of Durham and great-grandfather of St Aelred of Rievaulx. Baldred’s bones (‘ossa… Balterii’ in Latin) are included in a mid-twelfth century Durham relic list, where they are noted as being in the shrine of St Cuthbert together with Cuthbert’s incorrupt body, the head of St Oswald and the bones of other saints. Despite being in the most sacred spot in Durham, there is no trace of an active cult of Baldred at Durham after this point and his feast is not found in Durham calendars, not even the calendar from Coldingham Priory further down the coast in the Scottish Borders.

A local cult can, however, spread with local people. Baldred is mentioned in a great Scottish Chronicle, the Scotichronicon of Walter Bower (1385-1449). Bower was the Abbot of Inchcolm, another island in the Forth, and he was born in Haddington, the nearest town to Baldred’s churches. He is also mentioned in the writings of the philosopher and theologian John Major (1467-1550), who was born at Gleghornie, about a mile south of Baldred’s church at Auldhame, and went to school in Haddington. Interestingly, both of these mention that Baldred’s body multiplied after his death, a story hard to avoid if you grew up in pre-Reformation East Lothian where three churches claimed his relics. It may be East Lothian merchants who caused Baldred to appear in the calendars of some books of hours produced for the Scottish market at Rouen. He is also in the calendar of an Augustinian psalter made for Holyrood Abbey, by Edinburgh, about 1200. This was a few decades after King David I granted to the canons of Holyrood the parish of Hamer or Whitekirk adjoining St Baldred’s parishes. Canons seem to have regularly served this church and would have been familiar with the cult of Baldred. His name was also added to a fourteenth century breviary when it came to Aberdeen, which is harder to explain. These, together with people outside the area who bore his name such as Baldred Bisset (1260-1311), the Scottish lawyer, and the fifteenth-century knight, Sir Baldred Blackadder, suggest that his cult, while local, was not solely confined to a part of East Lothian. Baldred and his legend are also found in the 1510 Aberdeen Breviary but the team of scholars gathered by Bishop Elphinstone to produce the breviary sourced material on Scottish Saints from all over the country and most probably obtained the Baldred texts from East Lothian.

The evidence thus suggests a lively medieval local cult centred on the shore by the Bass Rock and associated with people from East Lothian, but not unknown among the wider Scottish community at home and abroad. Today his fame is spreading, for example he has recently been the subject of an American Catholic children’s podcast and an Eastern Orthodox icon, available on the internet in a poor quality image. The Orthodox have shown a great interest in British and Irish saints in recent years in response to the prophecy of St Arsenios of Cappadocia (1840-1924), ‘The Church in the British Isles will only begin to grow when she begins again to venerate her own Saints’. It is thus the right time to introduce Baldred to a wider audience and make known the historical evidence and his spiritual power. Part two of this series of articles will look at the evidence for the historical Balthere -who was the real St Baldred?

Part 2: Who was the real St Baldred?

Part 1 looked at the importance of St Baldred as a local saint in East Lothian but we were left with the question: who was the real St Baldred? Fortunately we know more about Baldred than about many other early Scottish saints. He was a Northumbrian hermit whose name was Balthere, ‘Baldred’ is a later medieval version of this, and he was associated with the community of St Cuthbert at Lindisfarne. His English name Balthere suggests that he was not, as some have suggested, an Irishman or a Pict. Although East Lothian is now in Scotland, from the seventh century it was part of the English Kingdom of Bernicia, the northern part of Northumbria

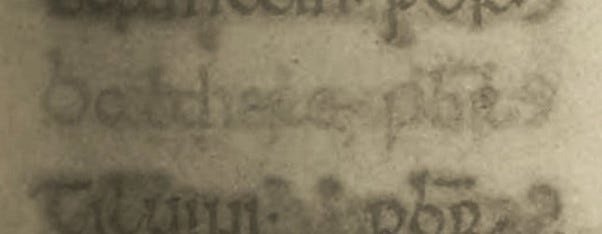

The Northumbrian Annals record the death on the 6th of March 756 of ‘the man of God and priest Balthere, who lived as an anchorite at Tyninghame, and entered the way of the holy fathers by departing to him who had formed him in the image of his Son’. This, together with his Anglo-Saxon name, places him in the first century of Northumbrian rule in Lothian. He would have been a contemporary of disciples of St Cuthbert (634-87) such as Ethelwold, Bishop of Lindisfarne 721-740, and of the production of the Lindisfarne Gospels. He appears in the list of anchorites associated with Lindisfarne in the early pages of the ninth-century Durham ‘Liber Vitae’, shown below. He is named as ‘Balthere p[res]b[yte]r’ and the date of his death is confirmed by his thirteenth place in the list which is headed by Cuthbert’s successors on Farne. Balthere is fourth before the hermit Echa, who died in 767 and is mentioned after Balthere in a poem by Alcuin discussed below, and eighth before Bilfrith who made the metalwork for the Lindisfarne gospels and whose relics were placed with those of Balthere’s in Cuthbert’s coffin.

The fullest account of his life, and it is in no sense a biography, is in Alcuin’s poem on the bishops, kings, and saints of York, probably written in the 780s. The relevant section is found at the end of this post. It places him upon what must be the Bass Rock, though it is not named: ‘a place completely encircled by the ocean waves / hemmed by terrible cliffs and steep crags’. The poem describes how Balthere fought the demons to save the soul of a lustful deacon and how he fell off a high cliff but walked away on the sea until he found a boat. These early texts show that Balthere was a priest and anchorite, following the holy fathers by being formed in Christ, protecting people and fighting demons, and living in the borderland between land and sea. The poem is remarkable in its evocation of the sea and in making Balthere a saint of the ocean and coastlands. His spiritual context is the Northumbrian world of Cuthbert and Bede with its links to Iona, but as an ascetic saint fighting for his people against the powers of darkness he is typical of many throughout the Church in its first millennium.

These early texts place Balthere at Tyninghame and on what is probably the Bass Rock. This island, which dominates the view from the coast from Dunbar to North Berwick, is very significant for his cult, justifying his modern title, Baldred of the Bass. Alcuin’s poem shows this but so does a peculiarity in the Mass of St Baldred in the fifteenth-century Haddington missal fragment, shown below.

All the early texts describe St Balthere as an anchorite and priest but a later tradition, reflected here, said he was a bishop. The chants and readings here of the Mass of St Baldred the bishop (written above in Latin as ‘S[ancti] Baldredi ep[iscop]i’) are mostly taken from the common texts used for a bishop, but one chant, the tract which replaces the alleluia during Lent, is unusual and not found in the Sarum or Roman missals commonly used in medieval Scotland, ‘Ecce vir prudens’.

The Cantus database of medieval chants gives just one example of it, without giving a reference to the manuscript, for the feast of St Gregory the Great on 12 March, just after Baldred’s feast. The text is ‘Ecce vir prudens qui aedificavit domum suam supra firmam petram’ (‘behold the prudent man who built his house on a solid rock’) which is appropriate for Pope Gregory, successor of Peter the rock. This is an allusion to Matthew 7.24 where the wise man (vir sapiens) builds his house on rock (‘supra petram’) with the solid (firma) quality of the rock possibly taken from the alleluia for the Mass of the dedication of a Church ‘Bene fundata est domus Domini supra firmam petram’ (‘the house of the Lord is well established upon solid rock’). Why did those who put together the Mass of St Baldred choose this text? It can only be because they saw his hermitage in the ocean on the massively solid rock of the Bass. From the East Lothian coast the Bass looms large and by an optical illusion often appears much bigger than it is and closer to the shore. The Bass rock as a fact in the life of Balthere is interpreted spiritually as if it were itself Scripture in the light of Matthew 7.24 as it has been received in the catholic liturgical tradition.

Balthere is thus a holy man in the tradition of St Cuthbert and Lindisfarne but also a saint rooted in a particular place, a corner of East Lothian centred on the Bass Rock, and the Rock is part of his identity.

Bibliography

Cantus: A Database for Latin Ecclesiastical Chant,

https://cantus.uwaterloo.ca/

The death of Balthere in the Northumbrial Annals is found in: Symeon of Durham, Libellus de exordio atque procursus istius, hoc est, Dunhehnensis, ecclesie: Tract on the Origins and Progress of this the Church of Durham, ed. D. Rollason (Oxford, 2000), pp. 80-81 (Lib. II c. ii).

Appendix: Alcuin’s verses on St Balthere.

Now I shall touch on you in lyric measure, holy Balthere

and mark a place for you in this my poem

with your calm spirit, I pray, preserve and guide

my frail craft through the ocean depths

among the sea monsters and waves as high as cliffs

that it may safely reach harbour with its cargo.

There is a place completely encircled by the ocean waves

hemmed by terrible cliffs and steep crags, where

Balthere, the mighty warrior, during his time on earth

vanquished time and again the hosts of the air

that waged war upon him in countless shapes.

This saint fearlessly crushed his enemies forces and the arms

of wicked demons, always opposing them with the weapons of

the Cross, the helmet and shield of faith, in successful combat.

That pious man was once alone and praying fervently,

his only thoughts were of heaven,

when, of a sudden, he heard a terrible uproar and din

like that of a host charging the enemy.

From the upper clouds there fell at his feet

a soul which quivered in great fear.

Hard on its trail followed a terrifying, menacing throng

bent on torturing the unhappy man with various punishments.

But that pious father clasped it to his bosom in gentle embrace

and immediately asked it what it was, why it was in flight

and what wrong it had done. To him the soul replied:

‘I was once a deacon, but with evil intent,

I once laid hands on a woman’s breasts – no more.

When I lived on earth I was afraid to admit my sin.

And so the cruel demons have been pursuing me relentlessly

for thirty days in order to torment me. I have

not been captured, but I have never been free from anxiety.’

Then one of the demons, terrifying him, cried out:

‘Today you will not escape, no, not if you were clasped

in the arms of St Peter. You will suffer the punishment

you deserve, evil one.’ The saint grew angry at the insult to

Peter, and said: ‘I am a hundred times less worthy that that

prince of the apostles, but with trust in God’s goodness

I say to you, tyrant ruthless and cruel, that you shall not

carry this soul off to hell with you today!’

The, in kindly meditation, he prostrated himself upon the ground

and implored God with tears for the guilt of that soul,

ceaselessly pouring forth holy prayers,

until he saw with his own eyes that it was carried high over

the stars in heaven in the arms of angels.

In his clemency Christ achieved another miracle through this pious father,

which was the exact equivalent of one performed in ancient

times. For just as Peter trod the waves of the sea,

so did this holy father. Once while walking

along the steep border of a high cliff,

he chanced to fall. Buoyed up by the ocean waves

he passed over the water with dry feet,

walking on the waves as if stepping in a country field, except

the wave received him more smoothly when he hurtled down

that the unyielding earth would have taken a falling man.

When he fell, the wave flowed to prevent it injuring him,

remaining as firm as earth beneath his steps lest he drown

and so he walked on the sea, as if on a solid path of earth

until he came to a boat adrift on the waves,

into which he climbed – his journey made safely on foot.

There was not a drop of water on his clothes, no dampness

on his boots: what nature denies Christ’s power can dispense;

at Christ’s command sea-waves become a path for the just;

the earth is turned into a whirlpool to punish the wicked,

the sea bears up the humble while the earth engulfs the proud.

But now, holy Balthere, we reverently implore you

that, just as the wave carried your body from the sea,

bearing you back in perfect safety to familiar shores,

so with your prayers you may help our souls escape

the storms of this world and enter the port of salvation.

From: Alcuin, The Bishops, Kings, and Saints of York, ed. P. Godman (Oxford, 1982), pp. xxxix-xlvii, 104-9.