This is the final part of Stephen Holmes article on St Balthere, or as we know him as, St Baldred of the Bass. See parts one and two here, and three and four here. This originated on his blog site Amalarius and is presented here in abridged form.

For the last part in this series on St Baldred of the Bass I want to bring together all the historical material from the previous posts and ask who he really is. More precisely, what is his spirituality and how is he relevant to those of us today who are Christians or live in the place where he is remembered?

‘No one knows what he himself is made of, except his own spirit within him, yet there is still some part of him which remains hidden even from his own spirit; but you, Lord know everything about a human being because you have made him… Let me, then, confess what I know about myself, and confess too what I do not know, because what I know of myself I know only because you shed light on me, and what I do not know I shall remain ignorant about until my darkness becomes like bright noon before your face’. (St Augustine, Confessions 10.5.7)

The human person is a mystery, even to his or her own self. Only God, from whom no secrets are hidden, can know us fully. We never know another person completely, even those closest to us, and this obscurity is more marked for those distant from us in time. With a saint like Balthere, as has been shown in previous posts, we can at least know some things about them and about what others thought about them. This can be useful to us, as a help in our Christian life or if we are attacked by demons or Vikings. In God’s providence saints pray for us and help us. A saint is someone who lives for God and for others, so it is worth getting to know them.

Spirituality is a word that can mean anything or nothing, but I understand it as the Christian’s life in the Holy Spirit. This is something which is unique for each person but always formed by revelation in Jesus Christ and communion with the Holy Trinity in the Church. From what remains to us, can we say anything about the spirituality of Balthere, about the sort of saint he was and is? The problem is that the human mind naturally tends to conform saints to patterns, primarily the pattern of Christ but also the pattern of the lives of other saints such as St Antony and St Martin of Tours. Even the life of Jesus himself in the Gospels took some of its form from people and stories in the Old Testament, for example Christ as the new Moses. If we are trying to write a biography in the modern sense this may be a problem, but a close reading of the sources can tell us much about what is distinctive about a Saint within this tradition. We have seen this in the choice of chants for his Mass which tie him into the local landscape, specifically the Bass Rock. It should also be clear from this series of posts that a Saint does not die. We can only go so far in excavating the life of Balthere the Northumbrian hermit who lived before 756 AD, but in faith we know that Balthere did not die with his body, or bodies. His story continues to develop, just as Christians believe he continues to be active in our world as an intercessor and patron. The Aberdeen Breviary says of him that ‘he flourished in Lothian by powers and shining miracles’ and this continued after his bodily death, becoming part of his story.

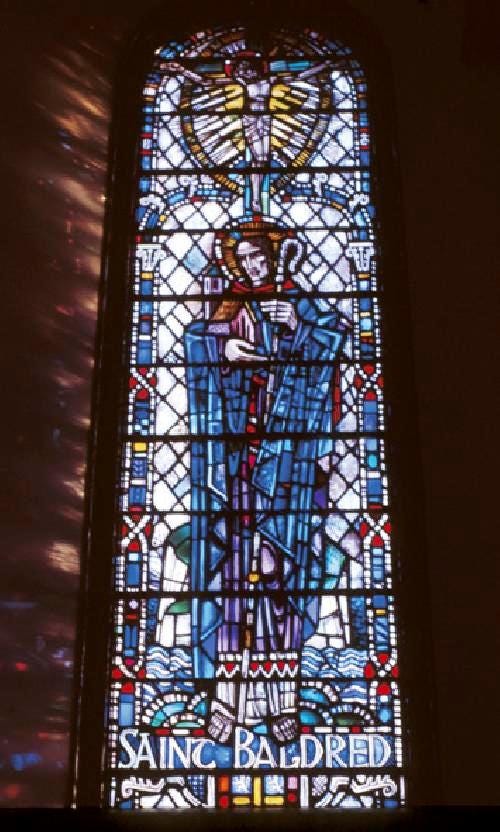

Thus one way to start to understand Balthere’s spirituality is with modern devotion. Here, surprisingly, I found the best place to begin was with the Presbyterians rather than with other churches, such as the Roman Catholics, which explicitly practice devotion and prayer to the saints. The Church of Scotland parish church of St Andrew Blackadder, North Berwick has a double window entitled ‘St Baldred of the Bass; The Apostle of the Lothians.’ It was installed in memory of the Revd James Robert Burt, Minister of North Berwick 1904-1935. Burt’s predecessor as Minister was the liturgical scholar George Washington Sprott (1829-1909) who was one of the founders of the Church Service Society which recalled the Church of Scotland to its catholic heritage. Part of this work involved a renewed interest in Scottish saints and Burt was in the same tradition as Sprott. The two windows are designed to emphasise a double aspect to Baldred’s life. In the left light he is called ‘St Baldred of the Bass’. Here he is depicted as a monk with staff and gospel against the background of the sea, with boats and the Bass rock, and above him are words from a hymn, ‘Be thou my vision O Lord of my heart’. This is Baldred the contemplative and ascetic. In the other light his title is continued and he is called ‘The Apostle of the Lothians’. Here his text is, ‘The Lord hath anointed me to preach good tidings’ (Isaiah 61.1; Luke 4.18). He is portrayed holding a cross, reflecting his association with the cross in Alcuin’s poem, and preaching to the people of Lothian. Below this image is a picture of the Lothian shore where his people lived, rather than the Bass rock, and in the main image these folk surround him, attentive to his words.

One could attribute this double image to a Presbyterian concern that our saintly ancestors were not just contemplatives and ascetics but were active in good works and useful in preaching the gospel. This is something that has obscured our understanding of the monastic life in early Scotland, for example seeing St Columba primarily as a ‘missionary’, but so has the firm late medieval and modern Catholic distinction between ‘the active life’ and ‘the purely contemplative life’ seen in commentaries on Martha and Mary in Luke’s gospel. In general the earlier tradition to which Balthrere belonged saw action and contemplation as two parts of the Christian life in general and the window does reflect the traditional image of St Baldred in more ways than just setting him in the East Lothian landscape.

Like the great Saint of his tradition, St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, Balthere seems to have combined periods of solitude and contemplation offshore with active pastoral concern for the people around his churches. The fact that Tyninghame was probably the mother church of this part of East Lothian suggests that Balthere and his monks were closely embedded in the local community and, at least in part, responsible for their pastoral care. This is not explicit in Alcuin’s poem, although the identification of Balthere with St Peter may hint at it, but Balthere’s compassion for the soul of the sinful deacon and the combination of Alcuin’s presentation of Balthere as a patron and the way the poem speaks of the dangers of the sea suggests his concern for those who sail this coast. The later legend in the Aberdeen Breviary is more explicit. It is anachronistic and inaccurate, the parish system was set up long after his death and he lived long after Kentigern, but surely reflects a local memory of Balthere as a pastor: ‘he never forgot his parish churches of Auldhame, Tyninghame and Preston, which he had received to govern from his father St Kentigern, whose cure of souls had also been committed to him by the working of God, preaching the faith of Christ to his parishioners; but he taught and instructed them with humility and zeal as befitted the service of God; and if he found sick people there he healed them and restored them to health by divine power, intervening by words alone [and] the sign of the cross’. In his old age it says that he ‘arranged to be cared for at the church of Auldhame’ ‘so that he might better instruct those over whom he held rule’, and after his death his people ‘all mourned the departure of such an outstanding shepherd from his flock’. At about the same time John Major, when discussing Baldred’s three bodies in his History of Greater Britain in the context of philosophical questions about whether it is possible for a body to be in more than one place, says of Auldhame, Tyninghame and Preston that ‘in these three place Saint Baldred taught the people by word and example’. As John Major grew up in these parishes at Gleghornie, he reflects how the saint was remembered in his day. Balthere was thus remembered and prayed to as a pastor and healer with a special concern for his own part of East Lothian.

Burt’s window is right in portraying him as a pastor and an ascetic but contemporaries would have been clear as to which had priority, Balthere’s power came from his prayer and ascetic struggle. This is the first-millennium vision of sanctity described by Basil Krivoshein in the third post in this series. Alcuin describes Balthere as ‘alone and praying fervently’ and also portrays his prayer as spiritual combat. He is a ‘mighty warrior’ who defeated the demons ‘that waged war upon him in countless shapes’. The Aberdeen Breviary continues this theme, Baldred ‘lived a contemplative and strict life… contemplating in constant meditation’. With reference to the contemplative Evangelist it is said that ‘he followed John the Divine as far as he could: he sought out lonely, deserted and isolated places, and took himself off to the islands of the sea’. This could be said of many saints but Balthere seems to have been known in particular as a great contemplative. His collect (prayer) begins ‘O God, who through the contemplative life of the blessed Baldred’. The ideal of the contemplative life was everywhere in the middle ages but these words seem to be unique among the multitude of Latin collects which suggests that he was above all known as a contemplative. This is as significant as the unusual Tract in his Mass which alludes to the Bass Rock. The Aberdeen Breviary offers further suggestions as to the content of his prayers, ‘above the rest of his meditations he ceaselessly imprinted the most bitter passion of Christ upon the secret places of his heart, in fasting, weeping and lamentations, by vigils and constant prayers’. This sounds rather late-medieval in its emphasis on the passion, but Alcuin had already associated Balthere with the power of the cross.

In the Episcopal Church of St Baldred in North Berwick there are no images of the saint in the early decorative schemes of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but two images from recent decades, a statue by a pupil from North Berwick High School and a carving in low relief by Esther Wiseman, show him as a classic early ‘Celtic’ monk and are each associated with the Bass Rock, in the former case with a separate bright stained glass panel by Ray Wiseman. Here sanctity and locality are primary and pastoral ministry is absent. The same is partly true of the 1959 window in the Church of Scotland parish church at Prestonkirk, one of Baldred’s original foundations. Here again Baldred is presented as a saint by the Bass rock, but this time as a bishop with a pastoral staff and as a founder, holding a small church representing Prestonkirk. The pastoral staff and connection to the parish pick up themes from the Aberdeen Breviary and John Major of Baldred as a local pastor. This window also draws from the early texts an association of the saint with the passion of Christ, having a crucifix above his head. Modern devotion to St Baldred expressed in art is thus rooted in the historical evidence and interprets it for the modern context. It is devotional in its use of the memory of the saint in his places but it does not explicitly call upon his help. That is our task.

At the start of this series of posts on St Baldred I suggested that the full Christian teaching about saints venerates them as powerful intercessors who help us, as well as being examples of the Christian life. If their prayers help us, knowledge of their stories can still act as an inspiration in our own Christian life. Through this they become our friends and, as no Christian believes the departed are really dead, the friendship becomes a natural context for a relationship and conversation to develop. Different saints emphasise different aspects of the life of faith and they can even make people feel welcome whose lives are not reflected in the public life of the church. In the North Berwick window we see a Minister of the Gospel not only identified with Baldred as a pastor but also with the saint as a solitary and contemplative, things difficult for a busy Minister. The window was given by his wife and we can imagine she saw better than anyone this tension in her husband’s life. Balthere speaks of the priority of contemplation, of rootedness in a place, of fidelity in spiritual combat against evil, of finding God in the wildness of nature, of fidelity to a vocation, of a ministry of healing and service to the community, of a life in communion with the crucified Christ, and of concern for those earning a living on the sea. In his links to St Peter, St John, St Kentigern and St Cuthbert he is an encouragement to those who struggle to live within the Church and its tradition. Not everyone will be drawn to Balthere but through the centuries he has helped many, otherwise he would have been forgotten.

In the Epistle for his Mass given in the last post we also see a hint of the local nature of his sanctity, ‘he shall be honoured in the Lord, and shall be glorified in the midst of his people… in the midst of his own people he shall be exalted’. He is less the ‘Apostle to the Lothians’ of Burt’s window and more the ‘Patron of East Lothian’. As such he cared for his people through miracles, or as the Aberdeen Breviary has it, ‘flourished in Lothian by powers and shining miracles’. In Alcuin’s poem the miraculous fall from the cliff and walking on the sea associated him with St Peter, as he was later linked to St John, but the moving of the rock in the sea, the multiplication of his body, his miraculous healings and the probable slaying of the Viking were all done for the benefit or vindication of his devoted people. He was thus not just a topographical feature but an enduring and powerful actor among those who lived in his sacred landscape. It is as such that he deserves to be remembered today, but more importantly to be called upon to help us. As we ask his prayers for ourselves and the people of East Lothian, let us pray together his collect from the Aberdeen Breviary (notwithstanding its promoting him to the episcopate):

O God, who through the contemplative life of the blessed Baldred, your bishop and confessor, has conferred ineffable grace on your servants; grant, we beseech you, that by his merits and intercessions we may be able to obtain in all things the saving help of your mercy.

Deus qui per vitam contemplativam beati Baldredi, presulis et confessoris tui, famulis tuis gratiam contulisti ineffabilem: praesta, quaesumus, ut eius meritis et intercessionibus opem misericordiae tuae in omnibus valeamus consequi salutarem. Per Dnm.

Holy Father Balthere, pray for us to God!

Bibliography

Alan Macquarrie, Legends of Scottish Saints: Readings, hymns and prayers for the commemoration of Scottish saints in the Aberdeen Breviary (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012), pp.70-71.

John Major, A History of Greater Britain, tr Archibald Constable (Edinburgh: Scottish History Society, 1892), pp.86-87.

St Baldred in the writings of John Major, translated by Archibald Constable

1. History of Greater Britain 2.7

‘About this a time lived Saint Baldred. It is related of him that his body was laid entire in three churches not far distant one from the other: Aldhame, namely, Tyninghame, and Preston; of which the two first named are villages distant from Gleghornie about one thousand paces; the third, one league. In these three places Saint Baldred taught the people by word and example, and on his death all three fell to arms in strife for the possession of his body. The same body was found numerically in different parts of the house, and thus each of these villages rejoices at this day in the possession of Saint Baldred’s body. I know that there are not wanting theologians who deny that such a thing as this is possible to God, namely, that the same body can be placed circumscriptively in different places; but their proof of this I cannot allow, as I have shown at more length elsewhere in my commentary upon the fourth book of the Sentences.’

2. Commentary on the Sentences 4.10.4

‘God can place the same body circumscriptively in two, three, and so on without end, totally diverse places. The proof of this conclusion: in the Life of Saint Martin we read that the Blessed Ambrose while celebrating at Milan was present at the burial of Saint Martin at Tours. The same appears in regard to the body of the Blessed Baldred, which is said to be at Aldhame, Preston, and Tyninghame, near to Gleghornie and those parts. This is a trite story, and an opponent will deny it, and I confess that he may do so without incurring the charge of contamination of the faith, since many doubtful things are put down in some Lives of Saints. The fact is proved by the appearance of Christ to Peter as Peter was flying from Rome, for the place is known well enough, namely, Domine, Quo Vadis?’