Continuing Reverend Stephen Holmes article into the life of Saint Balthere (Baldred of the Bass). See Parts 1 and 2 here. This originated on his blog site; Amalarius and is presented here with kind permission in abridged form.

Part 3: Balthere and the Christian Aesthetic

Balthere is a saint of the sea and the coastlands of East Lothian and this post will concentrate on the saint’s places, beginning with the most dramatic. In Alcuin’s poem the Bass Rock, in addition to representing the rock from the gospels, is understood as a ‘desert’ in the context of the Christian ascetic tradition as received in the insular churches (the churches of Britain and Ireland). In Adamnán’s ‘Life of Columba’ we meet the monks Báeán and Cormac who sail off in search of a ‘desert in the ocean’ (‘in oceano disertum’, i.20, 25b) or a ‘hermitage in the ocean’ (‘heremum in oceano’, 1.6, 17a). This is a major theme in insular monasticism and we find many island hermitages and monasteries around the coast such as Skellig Michael in County Kerry and Eileach an Naoimh in the Inner Hebrides. Alex Woolf has also suggested frequent pairings of a monastery, sometimes itself on an island, with an island hermitage: Iona and Hinba, Lindisfarne and Inner Farne, the Isle of May and Kilrenny, Inchcolm and Aberdour, and possibly St Serf’s Isle in Loch Level and St Serf’s community at Culross or Dunning. All of these, by location or tradition, have some connection to Balthere’s community (Living and Dying at Auldhame, 167).

We should, however, beware of just thinking of Balthere’s ‘desert’ as nothing but a way of escaping people and attending to God alone. In early medieval Britain seaways were major routes for travel and Balthere on the Bass may be likened to Antony Gormley’s sculpture the Angel of the North by the A1 today. The Bass Rock is also very visible all along the coast from North Berwick to Dunbar and we may compare Balthere to another ascetic, St Daniel the Stylite, who lived his life in the fifth century on top of a pillar just outside the great city of Constantinople, where he was visited by many including Emperors. Closer to home, the great Father of Balthere’s own tradition, Cuthbert, withdrew for prayer and ascetic struggle to the Farne Islands which, although he built a wall to restrict his own gaze, were in sight not only of his monastery on Lindisfarne but also of the royal power-centre of Bamburgh. David Petts has identified a similar arrangement in East Lothian, with the hermitage on the Bass, monastic sites at Tyningham and Auldhame and the secular power-centre at Dunbar, as shown in the map below . The map, although accurate, is actually quite deceptive. If you stand today on the site of the Bernician settlement at Dunbar, the Bass Rock looms up offshore at the end of the coast much larger than one would imagine from looking at the map. The rock with its hermit would thus be a permanent presence in the eyes and minds of the secular leadership, ensuring they could not ignore the power of God and his Church.

The classic text on ascetic struggle in the desert for Balthere and his contemporaries was the Life of St Antony by St Athanasius of Alexandria. Although written in Greek, it had been translated into the Latin they spoke by Evagrius of Antioch in 373 and was well known in Britain and Ireland. Basil Krivoshein explains its teaching on the desert in a way that also applies to our anchorite, ‘Monasticism itself was considered by St Athanasius and his contemporaries not merely as the way to individual salvation and sanctification, but primarily as a fight against the dark demonic forces. Certainly, every Christian had the duty to take part in this spiritual war, but the monks constituted the vanguard or shock troops, who attacked the enemy directly in his refuge, the desert, which was regarded as the peculiar dwelling place of demons after the spread of Christianity into inhabited localities. Retreat from the world was not understood as an attempt to escape the struggle against evil, but as a more active and heroic fight against it.’ (Krivoshein, ‘The Eastern Orthodox Tradition’, pp.24-25). Alcuin’s poem suggests that the main arena for Balthere’s ascetic fight was the Bass Rock but the sources reveal that various sites on the nearby coast were also included.

Tyningham is mentioned in Balthere’s obituary as the place where he lived as an anchorite and the Bass Rock was his place of ascetic withdrawal, but what was his church at Auldhame? Today it is just a bleak headland with the ruins of a sixteenth-century house nearby in some woods, but in the middle ages it was one of the three churches with his body and excavations in 2005 have revealed its importance. These found a cemetery, which was in use from c. 650 to 1650, and a sequence of medieval buildings beginning with a timber oratory constructed at the foundation of the graveyard and ending with a stone church which was rebuilt in the early sixteenth century and later abandoned. The burials suggested a first, monastic, phase of use which ended around 900, an ending euphemistically said to be ‘an event that may or may not have been influenced by Viking activity around the coast’ (Living and Dying at Auldhame, 171). Confirmation that this first phase was monastic is found in the discovery of an Anglo-Saxon glass inkwell, one of only six found in Britain, and a pile of dog-whelk shells of the type used to produce a purple dye used in book production. These suggest the presence of a scriptorium and thus a monastery, which is also suggested by a boundary ditch or vallum across the headland, filled in during the tenth century and typical of early monasteries.

Auldhame is first mentioned in 854, in the Northumbrian Annals which list a circuit of church sites claimed by the Church of Lindisfarne. This includes Edinburgh (St Cuthbert’s under the Castle?), Pefferham (Aberlady?), Auldhame, Tyninhgame and Coldinghame (Woolf, From Pictland to Alba, 82). That at this early date it is called the old (auld) minster-estate (hame) caused Alex Woolf to suggest that it was Balthere’s original church before his community moved to a more spacious home at Tyninghame, and Auldhame is certainly a convenient point from which to sail to the Bass (Living and Dying at Auldhame, 166-67). It may even be that, as the monastery of Lindisfarne pre-dated its patron Cuthbert, so, as the radio-carbon dating allows, the Auldhame monastery predates Balthere. Woolf even suggests that Auldhame remained as a church and burial place after the move to Tyninghame as part of a ritual landscape where pilgrims and monks could look out to the Bass Rock and ‘encounter the very landscape the saint had inhabited and reflect upon famous instances in his life and spiritual struggles’ (Living and Dying at Auldhame, 168). In this context he notes that Scoughall, the only other settlement in the small parish of Auldhame, is derived from the old English scucca meaning demon which may recall Balthere’s spiritual combat. Although St Baldred’s cave at Seacliffe beach was probably a nineteenth-century invention, the name dates from its discovery by a local landowner in 1831, other natural features such as the rock called St Baldred’s boat, his ‘cradle’, a rock with a deep fissure on the shore near Tyninghame, and the two wells of St Baldred may have been part of this sacred landscape.

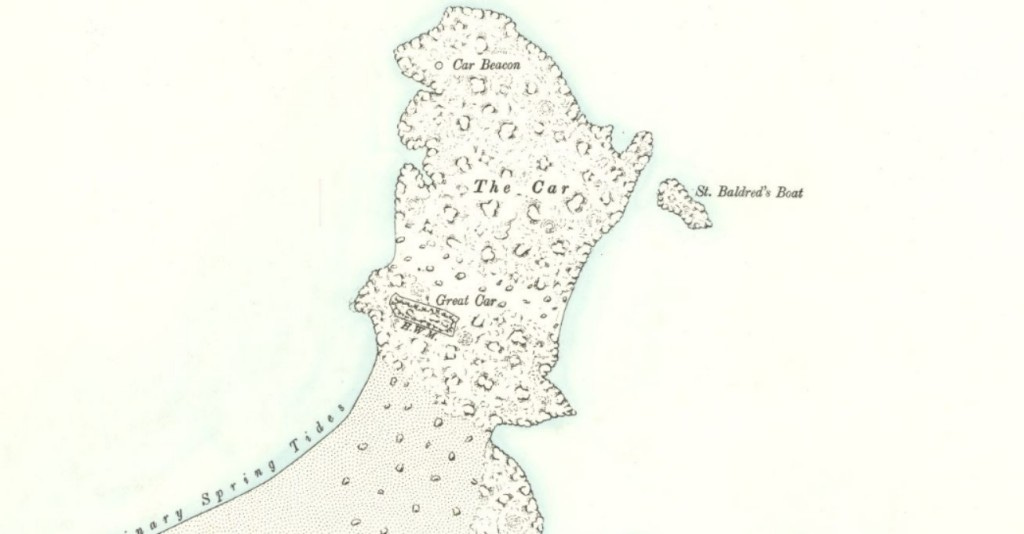

St Baldred’s ‘boat’ (scapha – Latin for a light boat or skiff), also called his tomb (tumba), is a rock which the legend of St Baldred in the Aberdeen Breviary claims that the saint stood upon and sailed out of the path of passing shipping. Today the name is sometimes attached to the crescent-shaped rock formation with a cross-topped beacon at the end, the South Carr beacon, just to the north of Seacliffe beach. It is, however, the detached rock just to the east of the Carr which is labelled as St Baldred’s Boat on Ordinance Survey maps such as the 1894 25 inch ‘Haddingtonshire III.10. Confirmation of the boat being a small rock is found in James Millar’s ‘Saint Baldred of the Bass and Other Poems’ (Edinburgh, 1824) where he writes, ‘a small rock, at the mouth of Aldham bay, still bears the name of Baudron’s Boat’, and RP Phillimore in The Bass Rock, its History and Romance (North Berwick, 1911) who notes that the boat ‘stands close to the Carr beacon’.

The early burials at Auldhame are mixed and do not suggest a celibate male community, so it may have been a ‘para-monastic’ community of married lay people and clergy attached to the main monastery at Tyninghame in a manner common in the insular world. Tyninghame has not been excavated in a similar way to Auldhame but ninth-century cross fragments found in the remains of its twelfth-century church suggest that this church was built on the site of the dependency of Lindisfarne at Tyninghame listed in 854, associated with St Balthere, and burnt in a Viking attack in 941 (Living and Dying at Auldhame, 137, 140, 166). If, as is probable, the main monastery was sited there, Woolf has even suggested that Auldhame survived the move of the community to Tyninghame as an ‘associative relic’ of Baldred, in a similar way to the church of St Aidan on Lindisfarne. The Auldhame community may thus have acted as ‘the curatorial staff of the hagiological landscape’, celebrating Mass and showing pilgrims round the sites associated with Balthere. The eleventh-century History of Saint Cuthbert (Historia Sancti Cuthberti) notes that all the lands between Lammermuir and the Esk were dependent on the Church of St Baldred at Tyninghame. This suggests that it acted as a mother church for a large shire-like area in a way similar to St Ebba’s Church of Coldingham in Berwickshire (Living and Dying at Auldhame, 166-70). This gives a firm grounding for the local cult of Balthere and the idea of a sacred landscape.

The idea of a ritual landscape sounds artificial to the desacralized modern mind and conjures up images of a holy theme park, but this irreverence is the product of a mind artificially limited by modern science and separated from God and the natural world of creation. Even for a Christian it takes an effort to separate oneself from the secular and disenchanted world in which we live. The Orthodox theologian and ecologist Philip Sherrard makes an attempt to describe the traditional view in his book The Rape of Man and Nature: ‘The medieval Christian world was a kind of sacred order established by God in which everything, not only man and man’s artefacts, but every living form of plant, bird or animal, the sun, moon and stars, the waters and the mountains, were seen as signs of things sacred (signa rei sacrae), expressions of a divine cosmology, symbols linking the visible and the invisible, earth and heaven. It was a society dedicated to ends which are ultimately supra-terrestrial, non-temporal, beyond the limits of this world. Indeed, a great deal of effort in this world went into preserving, fostering and nourishing the sense of realities which we now call supernatural. Throughout the length and breadth of this world visible images of these realities were set up and venerated, in icons, crosses, churches, shrines, in the collective ritual. They were the endless pursuit of monasteries, as of the saints and holy men who moved among the populace as naturally as birds among the leaves. Even when these saints and holy men retreated into solitude, everyone living in the world was aware that in the woods and hills, the wilderness and caves surrounding his home were peopled with these men ready to give counsel and benediction.’ (Sherrard, The Rape of Man and Nature, 63)

It is, however, possible to get too rosy a view of this pre-modern world. The idea that the original foundations associated with St Balthere seem to have ended with ‘Viking activity around the coast’ is supported by evidence from the Auldhame graveyard and by the mention in the chronicles of a Viking attack on Tyninghame in 941. As the archaeologists excavated the cemetery around Baldred’s lost church at Auldhame, among a thousand years of burials one stood out as unusual. SK752 was the burial of a young man, aged 26-35, with a spear, spurs and a belt of the type worn in the Irish Sea region around 900 AD. The Viking Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin and Northumbria is recorded as having sacked Tyninghame shortly before his death in 941 and although this may be the body of a local man who served in a royal retinue, it has also been suggested that this may be one of the retinue of King Olaf or even the King himself. This burial occurred at the end of the life of Auldhame as a monastic settlement and two other burials from the same period had axe wounds to the head which could have come from the Viking attack. The Melrose Chronicle says that ‘Olaf burnt and destroyed the Church of St Baldred at Tyninghame, he soon died’ (the Latin is given below), by which the monastic author seems to imply that these two events were connected. Baldred did not protect his followers, perhaps because of their sins, but he did avenge them by the sudden death of the young King Olaf.

Killing people who burn his churches is not high on the list of virtues people look for in saints today but those whose families had been killed by Vikings with axes may have seen things differently. Moreover, if this Viking’s death was seen as the result of provoking the Saint, his burial next to one of Balthere’s Churches may be an attempt to enlist the Saint’s prayers to secure his salvation, just as he did for the lustful deacon in Alcuin’s poem. Balthere was a man of power who could move rocks in the sea and smite the ungodly, but he was also a saint of compassion for sinners. Moving rocks is commended by Jesus (Matthew 17.20-21) and a major theme in Scripture is that the Lord chastises people in order to lead them to repentance. Balthere’s rootedness in place is inextricably linked with his power as a Christian saint.

Bibliography

A.O. Anderson, Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers AD 500-1286 (London, 1908).

Anne Crone, Erlend Hindmarch with Alex Woolf, Living and Dying at Auldhame: The Excavation of an Anglian Monastic Settlement and Medieval parish Church (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2016)

Chronica de Mailros, (Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club, ) p.29, ‘Anlafus incensa et vastata aecclesia sancti Baldredi in Tiningham, mox periit’

Basil Krivoshein, ‘The Eastern Orthodox Tradition’, in E.L. Mascall, ed. The Angels of Light and the Powers of Darkness: A Symposium by Members of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius, London, 1954, pp.22-46.

David Petts, ‘Coastal Landscapes And Early Christianity In Anglo-Saxon Northumbria’, in Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2009, 13, 2, 79-95.

Philip Sherrard, The Rape of Man and Nature: An Enquiry into the Origins and Consequences of Modern Science, 3rd edition (Limni, Evia, Greece: Denise Harvey, 2015).

Alex Woolf, From Pictland to Alba 789-1070, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland 2 (Edinburgh, 2007)

Part 4: The Veneration of St Balthere

The previous two parts have explored the original Balthere and his world. Now we will look at the veneration of Balthere, now called Baldred, as it was in the early sixteenth century. We can do this because of the work of Bishop William Elphinstone of Aberdeen (1431-1514) who complied the Aberdeen Breviary, published in 1510, which includes six lessons for his feast. A translation of the six readings is given below, with thanks to Alan Macquarrie. We know that Elphinstone’s team collected material from all over Scotland and so we can presume an East Lothian origin for this material, probably from one of his churches such as Tyninghame where his feast was kept and a written life preserved. To get a fuller picture of early sixteenth-century devotion to Baldred, the lessons can be read together with other sources such as the Mass of St Baldred from the fifteenth-century Haddington fragment. Given the loss of so many religious books and artefacts from pre-Protestant Scotland we are fortunate to be able to reconstruct the Mass and Office (the daily services in a Breviary) of St Baldred.

In the second post we saw that one of the chants of the Mass, the Tract, reflected the centrality of the Bass Rock in devotion to Baldred. It is possible that the first reading of this Mass might also reveal an emphasis in this devotion. The texts of the Mass of a saint are often taken from the ‘common’, a series of texts suitable for a particular category of saint such as virgins, bishops or martyrs. By the later middle ages Baldred was believed to have been a bishop and most of his Mass texts in the fragment are, as expected, from the common of a bishop and confessor (that is a bishop who did not die as a martyr) as given in the Sarum Missal used in Scotland. This reading, however, is from the common of a bishop and doctor; in Latin the word ‘doctor’ mean ‘teacher’ and the category here refers not to healers but to one of the great teachers of Christianity such as St Augustine and St Jerome. This reading must have been chosen because it suited Balthere better than the other options in the common of a bishop and confessor. It is a composite reading made up of two sections of the Old Testament book called Ecclesiasticus or Sirach (chapters 47.9-12a and 24.1-4). The translation below is from the reading in the Missal and departs in a few ways from the standard Vulgate Latin biblical text.

‘The Lord gave praise to his holy one, and to the most High, with a word of glory. With his whole heart he praised the Lord, and loved God that made him: and he gave him power against his enemies: And he set singers before the altar, and by their voices he made sweet melody. And to the festivals he added beauty, and set in order the solemn times even to the end of his life, that they should praise the holy name of the Lord, and magnify the holiness of God in the morning. The Christ took away his sins, and exalted his horn for ever. Wisdom shall praise his soul, and he shall be honoured in the Lord, and shall be glorified in the midst of his people, and shall open his mouth in the churches of the most High, and shall be glorified in the sight of his power, and in the midst of his own people he shall be exalted, and shall be admired in the holy assembly. And in the multitude of the elect he shall have praise, and among the blessed he shall be blessed’.

This reading may have been chosen to reflect devotion to Baldred as the founder of Churches, but the emphasis on liturgy and choirs would also make sense in a monastic setting so it may well go back before the destruction of the monastery of Tyninghame in 941. Above all, it is appropriate for a local saint, ‘in the midst of his own people he shall be exalted’. It is as such that Baldred is remembered in the Aberdeen Breviary its readings, read at the night office of Mattins, reveal that his cult has seen a number of developments from the earlier devotion to the coastal hermit-priest in the Lindisfarne tradition.

In the readings from the Breviary, Baldred is now not only a bishop but the suffragan or assistant of St Kentigern who is said to have died at the age of 183 in 503. As Kentigern probably actually died at the beginning of the seventh century, an entry in the Annales Cambriae suggests 612, and we know that Balthere died in 756, this is unlikely. Likewise Balthere’s own Lindisfarne/Durham tradition recalls him as a priest and anchorite, not a bishop, and so it is highly unlikely he was ever consecrated bishop, though like a bishop he may have had oversight over a number of churches. David Hugh Farmer, in his entry on Balthere in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, posits two Baldreds, one the Northumbrian hermit Balthere and the other a bishop and follower of Kentigern. This is not necessary, something else is going on here and there is no need to divide Baldred in two. Alan Macquarrie suggests that the Bernician (Northumbrian) conquerors of Lothian wished to associate their church with native saints and there is a persistent legend that Kentigern came from what is now East Lothian. The Aberdeen Breviary says of Baldred on the Bass Rock that ‘over a long period of time he committed to memory his teacher St Kentigern and the holiness of his life.’ Macquarrie suggests that Balthere may have written a life of St Kentigern and this is not improbable. He notes that Jocelin of Furness’s Life of St Kentigern contains evidence of traditions about the saint with a strong East Lothian colouring that are no later than the first half of the eight century and thus could have been written in Balthere’s lifetime. An erroneous pious belief in the early sixteenth century may thus be grounded in fact. It is also worth noting that a saint is not just whatever an historian can find out about his or her earthly life, the legends that grow up around a saint are also part of their identity and, however fantastic, deserve to be taken seriously.

The breviary legend does, however, follow the historical report when it says Baldred ‘sought out lonely, deserted, isolated places and took himself off to the islands of the sea. Among these islands of the sea he came to one called the Bass where surely he lived a contemplative and strict life’. It links him to the parishes of Auldhame, Tyninghame and Preston, which it says he was given by St Kentigern, perhaps a memory of an attempt to bind the new Northumbrian Christianity of Balthere and his companions to the British Church that was in Lothian before the conquest. The readings also describes the miracle behind the detached rock called St Baldred’s boat. This feature was discussed in the previous post and the legend may be a link to the sacred landscape of Balthere described there. The rock is said to have been further out in the sea, closer to the Bass, and to have been a danger to shipping. Baldred had himself placed on it and sailed the rock closer to the shore ‘and to this day it is called St Baldred’s tomb (‘tumba’) or St Baldred’s boat (‘scapha’)’. The saint was thus still remembered in the landscape.

The Aberdeen Breviary says that Baldred died at Auldhame, whereas the Northumbrian Annals suggest he died at Tyninghame. As Auldhame was probably the earliest site of his monastery, it may be that the Breviary preserves an old local tradition whereas the earlier annals simply placed his death in the main site associated with the saint. The Breviary account ends with the miracle of the multiplication of his body which may have some connection with this confusion. Baldred’s three parishes of Auldhame, Tyninghame and Preston all wanted his body ‘that, by showing him due reverence, they might have him as a pious intercessor in heaven whom they had held as their teacher on earth’, a good description of the job of a saint. On the advice of a wise elder they prayed for a sign as to which church the Saint favoured. Overnight his body became three bodies so each church could have one body with a shrine. The breviary concludes that ‘there they are held and venerated in the greatest honour and reverence to the present day’. Such multiplications of a holy body are not unknown in the lives of the saints, the sixth century Welsh saint Teilo also produced three identical bodies for the churches that claimed them. One may suspect that the body was divided and also wonder, given that the Breviary says the three bodies are still in the three churches, whether the pious transfer of the bones of Balthere to Durham in the eleventh century had been forgotten.

The legend of the three bodies was around by 1400 and known by Walter Bower who included it in his Scotichronicon. Another local writer who mentions the multiplication of Baldred’s body is John Major a century later who includes it in his History of Greater Britain and in his Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard (4.4.10). In both places he notes that the bodies are near to Gleghornie, where he grew up. In the Commentary on the Sentences, where he relates this bodily multiplication to the presence of the body of Christ in the Eucharist, he added that, ‘this is a trite story and an opponent will deny it and I confess that he may do so without incurring the charge of contamination of the faith, since many doubtful things are put down in the lives of the saints’. Respect for the saints could coexist with a healthy scepticism in an orthodox Catholic like John Major.

Our study of the cult of Baldred around the year 1500 is limited by the evidence, which is largely literary and liturgical. If only we still had the statue of him destroyed at Prestonkirk in 1770, some pilgrim tokens, records of pious donations, or accounts of a visit to the shrines like those of Erasmus to Walsingham or Aeneas Piccolomini to Whitekirk. It is, however, certain that there were three shrines to Baldred in addition to the chapel on the Bass Rock which was rebuilt and consecrated in 1542. The buildings, shrines and liturgy all contributed to a highly developed sacred landscape centred on the cult of Baldred in which also existed the popular cult of Our Lady of Whitekirk with its holy statue and well. All this was to be destroyed in the great religious revolution after 1559, but the memory of Baldred remained in the landscape and in people’s hearts. In the final post I intend to ask what were the characteristics of Baldred which were remembered through the ages and made him such a powerful local saint?

Bibliography

Alan Macquarrie, Legends of Scottish Saints: Readings, hymns and prayers for the commemoration of Scottish saints in the Aberdeen Breviary (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012)

Peter Yeoman, Pilgrimage in Medieval Scotland (London, 1999) – I thank Peter Yeoman for drawing my attention to the mould for making pilgrim badges pictured above, now in the National Museum of Scotland

Proper lessons for St Baldred from the Aberdeen Breviary (Macquarrie pp.70-73).

Reproduced with permission, thanks to Alan Macquarrie and Four Courts Press. 1. After the most reverend father and holy bishop Kentigern, aged 183 years, had been carried by the power of God most high Himself to the heavens, joined with the angelic choir, on 13 January in the year of our salvation and grace 503, at the city of Glasgow over which he ruled, after he had divinely shown many and varied miracles, St Baldred, who had been St Kentigern’s suffragan while he lived in the world, flourished in Lothian by powers and shining miracles, truly a most devout man, renouncing all worldly pomp and its vain cares; and he followed (St) John the Divine as far as he could: he sought out lonely, deserted and isolated places, and took himself off to the islands of the sea.

2. Among these islands of the sea he came to one called the Bass, where surely he led a contemplative and strict life, (and) where over a long period of time he committed to memory his teacher St Kentigern and the holiness of his life, contemplating in constant meditation. Above the rest of his meditations, however, he ceaselessly imprinted the most bitter passion of Christ upon the secret places of his heart, in fasting, weeping and lamentation, by vigils and constant prayers; so much so that he rendered himself pleasing and acceptable to God Himself and to men everywhere throughout the world. .

3. Indeed though, he never forgot his parish churches of Auldhame, Tyninghame and Preston, which he had received to govern from his father St Kentigern, whose cure of souls had also been committed to him by the working of God, preaching the faith of Christ to his parishioners; but he taught and instructed them with humility and zeal as befitted the service of God; and if he found sick people there he healed them and restored them to health by divine power, intervening by words alone [and] the sign of the cross.

q. And among the other signs of his miracles, one comes to mind as worthy to be repeated: a huge rock, massive by nature, which stood fixed and immobile midway between the island (of the Bass) and the adjacent mainland, appearing level with the waves of the sea, presented a very great hindrance to [his] ships and to the rest of those sailing; they used sometimes to be given over to shipwreck [with] their ships. Moved by pity for them, St Baldred caused himself to be placed upon this rock; having done this, by his will the rock is immediately raised up and, like a ship driven by a fair wind, it came to the hither shore; it still remains there as a memorial of this miracle, and to this day it is called ‘St Baldred’s Tomb’ or ‘St Baldred’s Boat’,

But at length, coming to old age through the labours and distress of this most miserable life, so that he might better instruct those over whom he held rule, he arranged to be cared for at the church of Auldhame, where not long after, in a house of his parish clerk, on 6 March, having poured forth prayers, saying farewell, he commended his soul to the Lord, with all patience and eagerness and compunction of heart; while they all mourned the departure of such an outstanding shepherd from his flock (and) from the fleeting world.

6. When the parishioners of the three churches, I say, heard that their most sweet and gentle pastor had ascended to the heavens from this life, they came in three crowds to the location of Baldred’s most lovely body; on all sides they each in turn with great longing earnestly desired and requested the body for their own church, so that, by showing him due reverence, they might have him as a pious intercessor m heaven whom they had held as their teacher on earth. Since they could not agree among themselves, on the advice of an elder they left the body unburied overnight, and all gathered separately in prayer that the glorious God Himself by His grace would send them some sign to which church the body of the blessed man should be carried. But in the morning, a thing seldom heard of appeared: when the dispersed people gathered together as before in their crowds, they found three identical bodies, laid out with the same funereal dignity. They gave thanks with great gladness to almighty God and St Baldred for this miracle, and each parish, singing songs and psalms, lifted one body with its shrine and carried them off to their churches with all reverence, and honourably placed them there; and there they are held and venerated in the greatest honour and reverence to the present day.