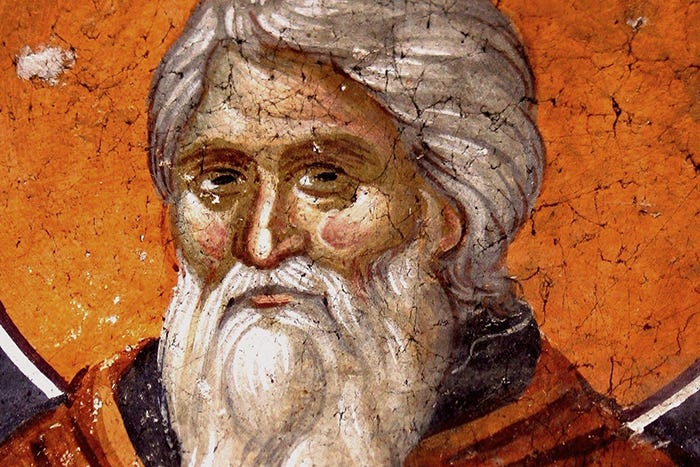

St John Climacus

Can a work written by a hermit monk, who lived 1,400 years ago, say something to us today?

Referring to St John Climacus’s The Ladder of Divine Ascent, Pope Benedict XVI asked, ‘[C]an…a work written by a hermit monk who lived 1,400 years ago, say something to us today? Can the existential journey of a man who lived his entire life on Mount Sinai in such a distant time be relevant to us?’[1]

John Climacus lived approximately from AD 579 to 649, dying as Abbot of the monastery on Mount Sinai in Syria. He lived as a monastic for much of his life, and The Ladder of Divine Ascent, sets out the path of spiritual progress for a monk. What follows is my personal take on having read through the Ladder twice fairly recently, these readings accompanied by listening to a very helpful series of podcasts by a Byzantine Catholic priest, Father Charbel Abernethy [2]. Whatever the spiritual worth of the work, I found it a rather engaging read: it’s often surprisingly witty, deep in its psychological insight, and refreshingly free of cloying piety.

I came away with three aspects of the work particularly in mind. First, there is the stage of subduing the passions. Second, there is what Jungians might refer to as ‘individuation’, integrating the various parts of one’s personality into a virtuous whole, primarily through accepting the discipline of a spiritual director. Third, there is moving that personality towards God so that, finally, it (almost) becomes God in the process of divinisation. Although there sometimes is a sense of a sequence to these steps, more strongly there is a sense of the continuing struggle in all three aspects: one never gets the feeling of ever being quite safe with Climacus as the passions and the demons which control them find ever more subtle ways of tricking the monk.

One way of exploring these three aspects is by analysing why they can be so difficult to the modern non-monkish mind. Let’s start with subduing the passions. It’s very difficult for a modern layperson to conceive of why it would be a good thing to subdue the passions in quite the harsh way that Climacus recommends. One of the most striking episodes in the Ladder is his visit to a monastery prison for penitent monks in Step Five:

Some chastised themselves in the scorching sun, others tormented themselves in the cold. Some, having tasted a little water so as not to die of thirst, stopped drinking; others having nibbled a little bread, flung the rest of it away….They did not even know that such a thing as anger existed among men, because in themselves grief had finally eradicated anger.

Fasting and extreme mortification of the flesh are prominent methods of breaking the control of the body over the nous (the intellect not in the sense of discursive reasoning, but that part of the person which can know God by means of direct spiritual perception). But such an extreme physical regime seems cruel to the modern mind. Father Charbel’s recommendations here struck me as particularly wise: this was one of those elements of the Ladder that will be and should be felt as most challenging to our modern condition, and that, rather than trying to solve this puzzle, we should live with it for a while and see what insights emerge from that tension. Having lived with it myself for a few months now, I suppose my main insights are that I am much further away from any sort of holiness than I would like to admit, and that my gratitude for the lifeline flung out by the Church and its sacraments is so much the greater.

The closely related second aspect of handing over oneself to a spiritual director is part of the destruction of the passions but is also part of developing the nous. Although the nous might be described as our True Self, it is a True Self that is at odds with what we normally take to be our Self: the flitting everyday empirical consciousness that is filled with whatever happens to stick in our brains for a while. Only by handing over that false Self to someone who has already that intuitive apprehension of God can we ourselves develop the nous. But again, to the modern mind, such a complete abandonment of Self seems unhealthy. The Self (as many philosophers will tell you) is simply the basket of whatever mental contents happen to be there at a time, not some strange metaphysical entity behind all that and (perish the thought) very, very close to God. And even were one to entertain such a possibility, the brutal reality of Climacus’ practical advice here looks like an invitation to spiritual abuse. For example, in Step Four:

Once the great elder, for the edification of the others, pretended to get angry with [a monk]…Knowing that he was innocent…I began to plead [his] cause…. But the wise director said: ‘And I too know, Father, that he is not guilty…the director of souls does harm both to himself and to the ascetic if he does not give him frequent opportunities to obtain crowns such as the superior considers he merits at every hour by bearing insults, dishonour, contempt or mockery.

Again, following the advice to live with this tension for a while, the best I can come up with is a sense of the distance between Climacus’ world and its perspectives, and the world I inhabit: that generally seems to result in a modern sense of how much better we all are, but only leads me to reflect on how much we may also have lost. More straightforwardly, there is the awareness that what we and the world take to be our Self is not our Self.

Finally, the aspect of divinisation. Having fully developed the intellect, the monk is divinised. From Step 29:

He who has been granted such a state, while still in the flesh, always has God dwelling within him as his Guide in all his words, deeds and thoughts. Therefore, through illumination he apprehends the Lord’s will as a sort of inner voice. He is above all human instruction and says: When shall I come and appear before the face of God?…The dispassionate man no longer lives himself, but Christ lives in him….

Although the Ladder can appear at times almost Pelagian in the efforts a monk has to make to achieve divinisation, the lasting impression it gives is of the desperate need for grace. Whenever we do something, there is always a demon waiting to congratulate us on our efforts and thus to nullify any efforts made. Only by allowing oneself to dwell with God by simply making Him the focus of one’s life is that final closeness achieved, less by one’s own efforts than by the overwhelming mercy of God Himself.

As we reach the final stages of Lent, how has the Ladder left me? I pray more, particularly the Jesus prayer: after being constantly battered by the cunning of your passions and the demons around us, what else is there other than to call on the only certainty which is God? I remain distrustful of spiritual direction in the form suggested by Climacus but am less willing to assert my everyday wants and desires against that teacher which is the world and its buffeting. (Step 28: ‘Have all courage, and you will have God for your teacher in prayer.’) Finally, I distrust more than I already did the sort of public displays of anger and pride that are all too common in our society and even in the Church. I do not know the precise way to deal with all the evils we face, but I suspect that God does not want us to react like that.

By Stephen Watt

Further reading:

All quotes from the text of The Ladder of Divine Ascent taken from http://www.orthodoxriver.org/books/ladder-of-divine-ascent/ (accessed 10 April 2025)

Wikipedia article John Climacus John Climacus - Wikipedia (accessed 10 April 2025)

Wikipedia article The Ladder of Divine Ascent The Ladder of Divine Ascent - Wikipedia (accessed 10 April 2025)

References:

[1] Benedict XVI, General audience 11 February 2009 (available online at https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20090211.html ; accessed 10 April 2025)

[2] Podcast on The Ladder of Divine Ascent PODCAST SERIES | PhilokaliaMinistries (Father Charbel has two series on the Ladder. I only listened to the earlier series Season 2 | Philokalia Ministries which I found excellent. The sound quality on some of the audience questions and discussion is of variable quality, but it’s worth trying to follow them as they often contain insightful points.)

Writing You Might have Missed in the Coracle

The Benefits of Fasting: Archbishop Charles Eyre, of the Western District of Scotland in 1871 writes about the benefit and reasons for fasting. An excerpt.

Miracle at Birnie: How a synthesis of local Catholics, the Ordinariate and Presbyterians are saving one of the oldest places of worship in Scotland.

A Lenten Journey of Hope: How has your Lent been?

Included in this month is the upcoming feast of St Magnus, St Donan and St Maelrubha. We also have summary of the life of St Egbert of Iona from OMNIUM SANCTORUM HIBERNIAE.

Other Things that Might Interest You

The Quiet Revival: A recent survey by the Bible Society in England and Wales has picked up on what it is calling a ‘quiet revival’. The remarkable feature of this is that it is Gen-Z who is driving it. There are no figures for Scotland but is anyone picking up on any anecdotal evidence?

Being Catholic TV: Set up by Scotland’s Bishop’s over lockdown the channel, based out of St Augustine’s in Coatbridge is steadily growing its offering and becoming a home for Catholics in Scotland to tune in to.

I've got to read The Ladder of Divine Ascent. Your article just reminded me to put it on my list. Thanks.