The Aberdeen Breviary

In the Coracle this week: Scotland's foundational Ecclesial text, Elon Musk vs Pope Francis and Grieving in Public.

In the Coracle this week: Dr Tom Turpie on one of the earliest printed texts in Scotland - the Aberdeen Breviary. James Bundy writes about grieving in public after the loss of his father; and Stephen Watt asks if mercy and empathy are fundamental weaknesses which is Elon Musks view but was never Pope Francis’.

Our Saints for August include St Blaan of Bute who could make fire blaze from his fingertips to aid in the Night Office, St Aidan of Lindisfarne and St Angus of Perthshire.

The Aberdeen Breviary: Origins and Legacy

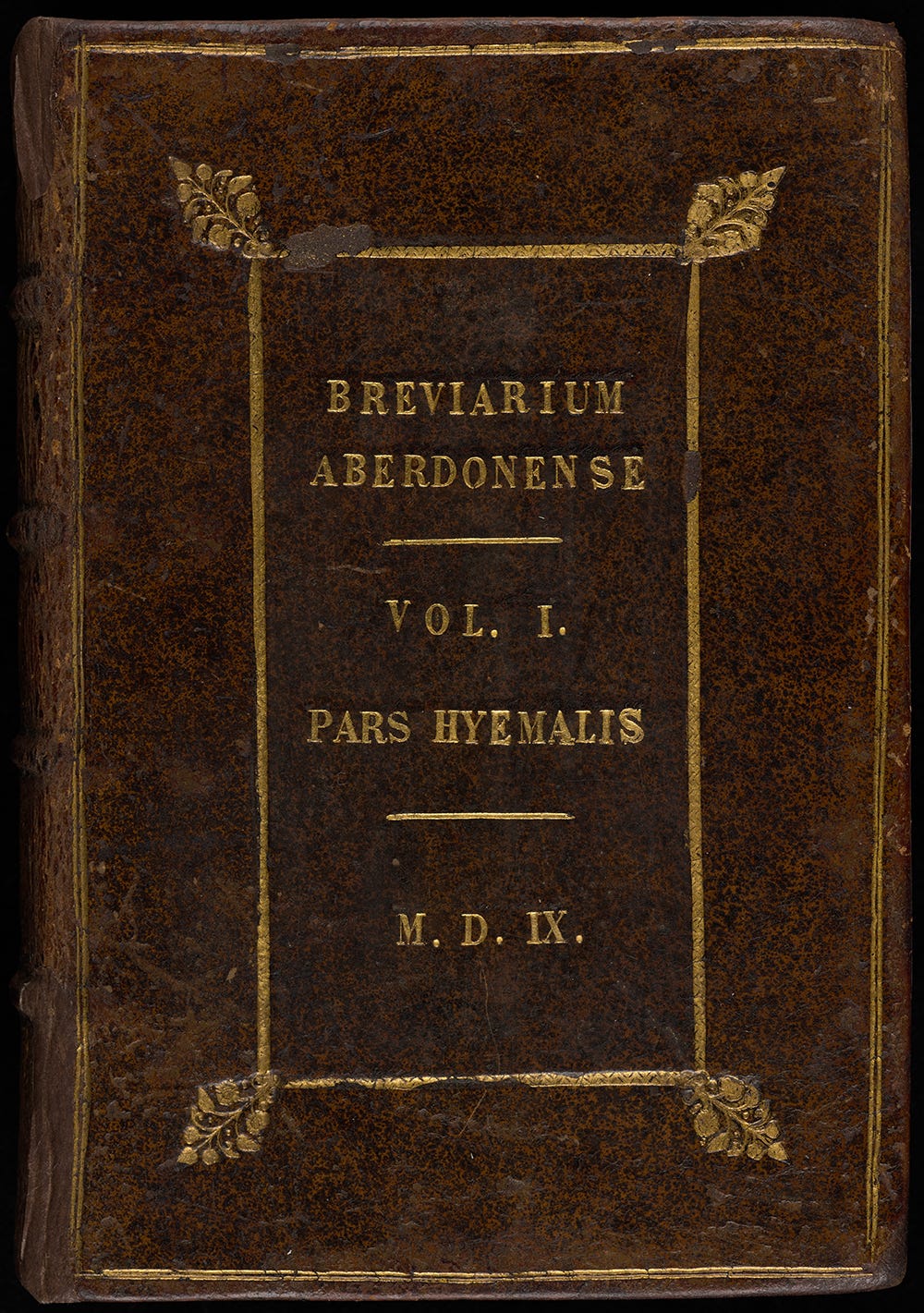

The Aberdeen Breviary is not only Scotland’s first printed book, but one of the most important religious texts to survive from medieval Scotland. It was an ambitious attempt by William Elphinstone, bishop of Aberdeen (1484-1514), in collaboration with James IV (1488-1513), to create a Scottish service book that could be used in churches across the kingdom. The short-term catalyst for the creation of the breviary was a charter issued by James on the 15th of September 1507 that authorised the creation of the first printing press in Scotland. In the charter he stated that, along with chronicles and books of law, it should be used for mess bukis, and portuus efter the use of our Realme, with addiciouns and legendis of Scottis sanctis. It is no surprise that service books (mess bukis), intended for use in the more than a thousand parish, collegiate and monastic churches that existed in Scotland by 1507, were considered a priority for the new press. Along with theological works, these were the most common books of a religious nature that existed in, and have survived from, medieval Scotland. The first such book to be printed by the new Chepman and Myller press in early 1510, was the Brevarium Aberdonense, more commonly known as the Aberdeen Breviary. In the longer term, the new breviary was a result of two trends. Firstly, a growing interest in local and regional saints in Scotland that had developed from the fourteenth century onwards, and secondly the increasingly close relationship between church and crown in late medieval Scotland.

Bishop Elphinstone

The Rhythms of Medieval Life

The Christian calendar with its major and minor fasts, feasts and holy days was the framework around which the people of medieval Scotland organised their lives. The major feasts of the church, Easter, Christmas, Whitsun, Martinmass (11 November) and Candlemass (2 February) dictated the patterns of work and rest, and served as the dates on which wages, debts and rents were paid. In parish churches, cathedrals and other religious communities, feast days were marked by the reading aloud of the lives of saints who were believed to have died on that day. A common recent misconception, based on the number of feasts included in medieval church calendars, is that people only worked for part of the year and spent most of it on church mandated ‘holy days’. This was of course not the case. Like their contemporaries across Europe, most Scots lived in the countryside and were involved in farming, working either on their own rented properties, or those of their landlords all year around. It was only the major feasts, combined with those of important local or regional saints that were expected to be marked as holy days and free of work.

By the sixteenth century there were two key service books that assisted the Scottish clergy in carrying out their duties. Missals, which contained the Office of the Mass, and Breviaries that contained the psalms, hymns, and readings for every day of the year. Developed in the eleventh century as part of the Gregorian Reform movement’s efforts to bring greater uniformity in religious practice across Latin Christendom, breviaries were intended to be a short (hence the name) guide for churches to the key elements of mainstream religious observance. There was however, no uniform breviary across Western Europe, with considerable regional, local, and institutional variations alongside the core feasts days and observations of the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. Two authorised calendars or ‘uses’ as they were called, known as Roman (official rite from the papal see) and Sarum (an English form originating in Salisbury), were most common in medieval Scotland. By the early sixteenth century, many of these service books appear to have been out of date. They were missing newer feasts, particularly Marian and Christ related devotions such as those of the Holy Blood and the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, that had arrived in the kingdom from Europe in the fifteenth century. In the same period there had also been a growing interest in local and regional saints in Scotland. This can be seen in surviving books where feasts of local saints have been added to Sarum and Roman calendars.

The creators; William Elphinstone and James IV

King James IV

The Aberdeen Breviary was an attempt by William Elphinstone create a Scottish service book that would, they hoped, replace the Roman and Sarum calendars. Elphinstone was a tireless administrator and reformer who, in addition to the new breviary, founded the University of Aberdeen in 1494 and was responsible for important organisational reforms in his north eastern diocese, many of which were extended to the Scottish church as whole. He also played a central role in royal government during the reigns of James III (1460-1488), and his successor, James IV. Elphinstone had been working on a reformed liturgy for his own diocese since the 1490s with a team of local clerics. It was the intervention of James that encouraged Elphinstone to make this a national project. James IV had a strong interest in Scottish saints, regularly visiting the shrines of saints like Ninian of Whithorn and Duthac of Tain. His reign was characterised by attempts to project Scottish power on a European stage, centralise government and law, and to bring the church under royal control. Such a vision can be seen in stone in palatial building projects such as those at Holyrood in Edinburgh, Falkland, Stirling and Linlithgow, and was apparent from a belligerent foreign policy that ultimate led to his death in battle during an invasion of England in 1513. A national breviary was therefore in keeping with James’ confident vision of Scotland’s independence and important role in the British Isles and Europe, and his efforts to create a national church under royal control.

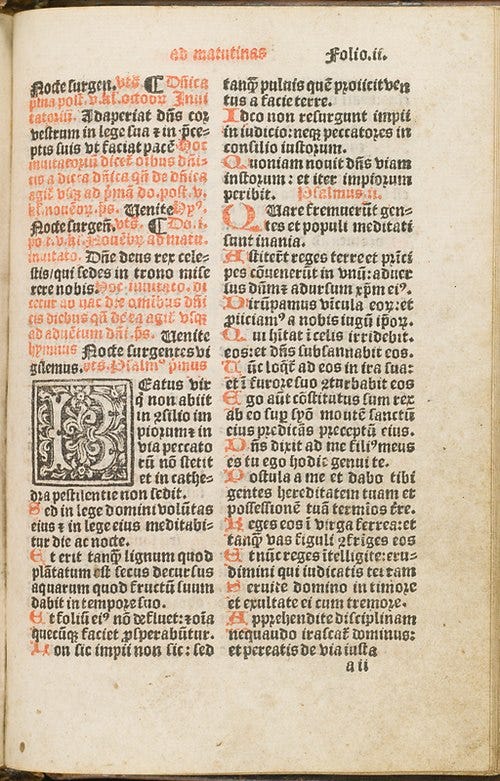

The Breviary

The new breviary was printed in two volumes (summer and winter) in 1510, providing materials for the celebration of the Divine Office in relation to 229 different feasts or eves of feast days in total. For most saints the main commemoration was to be held at Matins on their feast day, a service that took place early in the morning, before day break. This was preceded by a service at Vespers, on the eve of the feast day, with the commemoration concluded at second Vespers, during the evening of the feast day itself. For most of the feasts, the breviary includes hymns and antiphons that were not specific to the individual, but to the type of saint, (martyr, confessor etc). It then includes a set of short Lessons, either 3, 6 or 9 depending on importance of the saint. These lessons included passages from the lives of the saint, or where this was not available, suitable passages of scripture deemed relevant to them. For a small number of Scottish saints like Columba, Andrew, Machar, and Ninian, who were patrons of cathedrals or considered to be of national importance, the breviary includes ‘proper’ hymns and Antiphons specific to them, and materials for more services to be carried out at 2–3-hour intervals during the feast day. The book was modelled on an English Sarum Breviary, with the main difference in the saints who were included in the calendar, and the significance given to them. Many English saints were removed, or their importance reduced, replaced by 81 Scottish saints in total. It was clear that Elphinstone and his team were trying to create a book that could be used across Scotland, with an attempt to include saints from each diocese, including several quite obscure figures for whom there is very little information elsewhere.

Legacy

Ultimately the Aberdeen Breviary did not achieve the ambitious aim of its creators. It has been argued that, as a service book, it was unwieldy, with the focus on Scottish saints throwing out the balance, and sometimes leading to too many feasts on each day. The main reasons for the failure was however, the death in quick succession of the driving forces behind the project, James IV in 1513 and Elphinstone in 1514, and competition from imported books. These deaths meant that the project lacked official promotion, and later editions that might have ironed out some of the teething problems. Sarum and Roman books continued to be imported and used after 1510, and in 1533 the Quinones Breviary arrived in Scotland. This new breviary, authorised by the papacy, engaged with some of the problems the Aberdeen Breviary had been intended to remedy, and proved popular until the Protestant Reformation of 1560.

Its legacy in the long term however, has been the rich wealth of information it provides on Scottish saints, and on late medieval life more generally. For many of the 81 Scottish saints included in the breviary, the materials compiled by Elphinstone and his team are the only information that has survived from the Middle Ages, beyond the odd place-name or church dedication. While Hagiography (the lives of the saints), must be treated cautiously as a source, it can tell us what these individuals meant to the people who venerated them in early sixteenth century Scotland, as well as the lessons that the church as an institution hoped that people would draw from their exemplary lives. The stories also provide snippets of fascinating materials on everyday life. The lessons of St Duthac of Tain tell us about the challenges of travelling during storms and communal action during famine, those of Gilbert of Caithness include details on local fisheries and Maelrubha of Applecross on clan rivalries. Insight into the ailments and accidents that befell the people of the era can be found in the lessons of Triduana of Restalrig, and of several other saints. The rich materials included in the Aberdeen Breviary therefore allow us a fascinating insight into the social, political, and religious world of Scotland a generation before much of this world was swept away by the Protestant Reformation.

By Dr Tom Turpie