The Historical St Patrick

Stephen Watt asks who the real St Patrick was and does his writings correspond with the later stories?

In his Ten Thousand Saints, the Irish writer Hubert Butler wrote:

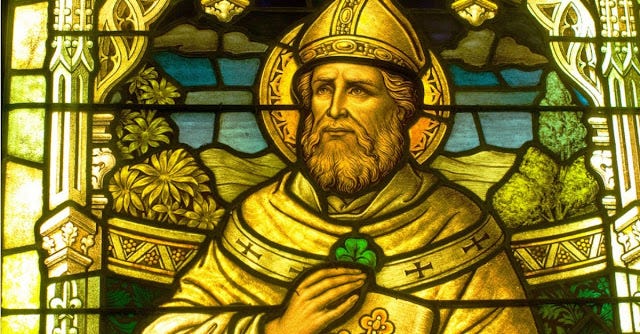

It is 17 March and I am contemplating a picture of our national saint on the front page of a national daily. A bearded and mitred figure of great dignity, he seems to be about to deliver some message to our sad generation…He is telling us that woollen blankets and undergarments manufactured by the Snowflake Fleece Company are staunch and absolutely reliable. Folds of snowy cloth hang from the arm, which holds the crozier, and it is plain that he too in his time knew that worth will tell and was the enemy of all that is mean and shoddy.

Although saints’ lives always gather fable, it is hard to think of many other saints who have gathered quite so much as St Patrick. So what do we know of the real Patrick? The commonly held academic position is summarised by Suzanne Forbes thus:

On the basis of [the Confessio], we can say that Patrick really existed, that he was born somewhere in Britain, and that he was taken to Ireland as a slave. He subsequently escaped and travelled back to Britain, but once he became a priest he felt compelled to return to Ireland as a missionary. Although many stories and beliefs about Patrick's life emerged in the centuries that followed (such as the idea that he drove all the snakes from the island), the Confessio and Epistola are the only primary sources that researchers have been able to attribute with confidence to Saint Patrick himself and the period of time he was in Ireland. As a result, they are the only sources to provide us with reliable information about the ‘real’ or ‘historic’ Patrick.

The Confessio and Epistola are two documents written in Latin, allegedly by Patrick, a claim which is widely held by scholars to be plausible given the content and style of the documents. Based on a variety of supporting evidence primarily from the Confessio and the account it gives of the surrounding social circumstances, he was active during the fifth century AD, with possible dates of birth being in the late fourth century, and dates of death based on later documents being c.460 and c.493.

The Confessio says that he was born in Bannavem Taburniae (a place of which no record exists) along with the oddly worded claim that going to Britain (or more exactly ‘in Brittanniis’ -among the Britons) is going ‘quasi ad patriam et parentes’ (as though to my homeland and relatives). These scant facts have led to a number of speculations, but point to a Brittonic speaking area within easy reach of the Irish pirates who abducted him at the age of sixteen. (Purely on the grounds of national prejudice, we at St Moluag’s support the Catholic Encyclopedia’s claim that he was born in Old Kilpatrick in West Dunbartonshire.) He was the son of a deacon and likely to have been of reasonable economic means and social status.

So much for his origins. But before going to examine the rest of his career, it’s worth emphasising that even the bare outlines given so far may be doubted. The sceptical Hubert Butler comments on the Confessio and Epistola:

As for [them], the most we can say about them is that a fifth century missionary might well have written them and that, if a later ecclesiastic invented them and attributed them to Patrick, he did it with skill and plausibility. The real force of the item for believing in their authenticity is that most people in Ireland want to believe, and that anyone who opposed this strong current of opinion would be heading for trouble.

This is probably going too far. Scholars of early mediaeval Europe struggle to make sense of a hodge-podge of sparse primary sources, embellished later sources and archaeological findings. Any account of persons or events in this time is going to be based on more or less plausible leaps of imagination and interpretation: less a matter of wanting to believe and much more a matter of having to make some educated guesses, failing which there would simply be silence.

Many of the familiar stories about Patrick’s later career (such as the magical contest of between the druids and Patrick at the Hill of Tara or the banishing of snakes from Ireland) seem implausible when judged by the sceptical tests of academic scholarship. No academic historian is likely to trust (publicly in any case) stories featuring magic or miraculous intervention. (Whether a Catholic should trust the story of any saint which doesn’t feature such miracles is a further question.) Herpetology provides a difficulty in noting that snakes have not lived in Ireland since the land link to Britain was cut off about 8,500 years ago after the end of the last ice age. Other stories may plausibly have been invented to further ecclesiastical politics, particularly the desire to promote Armagh’s claim for ecclesiastical supremacy in Ireland. The evidence of Patrick’s personality and circumstances in the Confessio and Epistola seems at odds with the later stories. As Ian Bradley puts it:

Patrick’s posthumous fame was achieved the cost of grossly distorting his actual character and achievements in life. The self-doubting wandering missionary of the Confessio became the confident miracle-worker at the power-evangelist of the [later lives].

When sifted through those tests, we may be left with little more than one Brittonic speaking missionary among many other missionaries, spreading Christianity in an extremely hostile pagan society, whose cult and legends have buried whatever the ‘real’ Patrick was, in Hubert Butler’s words, ‘under the religious prepossessions of the fifty generations that shaped his story’.

Well, even if that were all, that’s not nothing. One of the aims of St Moluag’s Coracle since its beginning has been to publicise some of the early Scottish saints, most of whose lives make Patrick’s seem positively over-documented. To remember and explore the long past of Christianity in these islands, to give at least some shape to those men and women who undoubtedly did spread the religion in an early mediaeval, pagan environment, to have a sense of what this must have been like -all that is not negligible even if it is often uncertain and subject to competing detailed interpretations. And Butler’s ‘religious prepossessions of the fifty generations’ since Patrick are also part of that long story: another reminder of how deep and enmeshed Christianity is with the general history of Ireland and Great Britain. Moreover, the legends, even the most improbable, usually carry a spiritual meaning beyond whatever historical reality lies behind them. One common aspect of this is the relocation of patterns of Biblical stories into our landscape: when Patrick fights the magic of the druids at Tara, the scene reflects the struggle between Elijah and the priests of Baal on Mount Carmel. When Patrick expels the snakes from Ireland, he reflects Christ in his ministry of exorcism. In a modernity where there is increasing talk of the need to re-enchant the world, how previous generations have accomplished this becomes an important resource for us, particularly where these stories, as with Patrick in Ireland, retain a popular currency beyond committed Catholics.

But beyond all this, Patrick as a saint is alive in heaven and able to help us. Whatever the earthly Patrick was like, why wouldn’t he care for Ireland, care for the message of Christ, still be concerned to spread that message in the face of a hostile world? That, whatever, the historical realities, is the living reality of the communion of saints in Catholicism. Let’s not ignore that.

St Patrick, pray for us!