Two Saints of the Dunkeld Litany – St. Dovenald and St. Crathlinthus

The joys and difficulties of Scottish hagiography.

One of the most attractive elements in Christian theology is the Communion of Saints. The members of this communion are almost without number. When God promises the Patriarch Abraham descendants that will number as the stars, and as the sand of the seashore, we have but a glimpse of the sheer multitude that participate in the Heavenly realm. To put it in a more fundamental way, they participate in God Himself, who is Triune (and therefore the principle of Communion) and who is immeasurable. If the Saints are like the sands of the seashore, God is like the ocean that defines them, crashing onto the shore’s boundaries, and coming on the tides. Simply put, there is no shore without a sea. The Saints are defined by the God who creates them. This is to say nothing of the Angels, who are very probably even more numerous than the Saints.

The immensity of this Communion has a few consequences. Perhaps the most obvious is variety. While all Saints must ultimately conform to Christ, and become like Him, they do so in so many different ways. If everyone is unique, and if all are called to Salvation, the variety of Saints is potentially unlimited. It can be interesting to find this variety in hagiography. It is true that the Church proposes certain categories, found in her litanies: Patriarchs and Prophets, Apostles and Evangelists, Disciples, Innocents, Martyrs, Bishops and Confessors, Doctors, Priests and Levites, Monks and Hermits, and Virgins and Widows. Theological research could probably be done on the meaning of each of these categories, and whether some are now closed: e.g. does the category of Patriarchs only pertain to the Patriarchs of the Old Testament? However, even if the categories propose a certain limit to how sanctity is defined, there is great individuality within them. No two Martyrs are the same, no two Confessors attest to the Faith in the same way. For this reason, hagiography has a necessary relation to biography. We might say that hagiography is that art which writes out a sacred biography, the narrative of how Divine Grace worked across a lifetime, leading to Salvation.

Yet, once we open begin to research hagiography, we soon run into a major difficulty. So many of the accounts which have been handed down to us are replete with legendary material, exaggeration and hyperbole, and sometimes theological error. Even if the act of Canonisation is infallible, which is a disputed point, the hagiographical dossiers are most certainly not. As a consequence, we often have a Saint whose name we venerate, but whose acta are spurious. Indeed, sometimes all we have is a name. So many of the Martyrs are known only for their death, with no recorded historical information about their lives. This isn’t a problem in itself, as God can keep His own counsel. However, it has interesting consequences for the topic of this article. We will briefly examine some of the most obscure Saints in the Scottish Church, if only to be thorough, and to delimit the margins of the subject.

The Dunkeld Litany is a document that invokes the intercession of very many Scottish Saints, and which includes a number of names which are almost unknown. Since we were recently looking at the case of James VII & II, we might begin with two royal Saints, St. Dovenald and St. Crathlinthus. It should be noted that the Dunkeld Litany, as we have it, is quite unusual, in that it claims to have been used by the ancient Culdees. Alexander Penrose Forbes, in his magisterial “Kalendars of Scottish Saints”, argues that:

“The presence of Crathlinthus shows that it must have been drawn up after the time of Boece, which is confirmed by the latinity of the prayer at the conclusion” (pg. xxxiv)

This is an important point to bear in mind at the outset. The claim is effectively that the name Crathlinthus snuck in to the Litany, during or after the lifetime of Hector Boece, who died in 1536. This raises challenging questions. Forbes notes elsewhere that the Dunkeld Litany was found in St. James’ Monastery, a Benedictine Abbey in Regensburg, Germany. We might argue that the document made its way there before the Scottish Reformation in 1560. This doesn’t leave much time to add in the name of Crathlinthus. Another possibility is that the Benedictines themselves edited the Litany after it arrived at their Abbey. In any case, if Crathlinthus comes from such a process, it is almost as though a cultus to him was invented out of thin air.

There might be a third possibility, and it would be for historians to judge: is it possible that Hector Boece established the character of Crathlinthus from obscure references to such a character in Scotland’s distant past? Might he have had access to sources which we have now lost? This is one of the more difficult points. As far as we know, the biographical details of Crathlinthus are an elaboration of Boece, who wrote an historical chronicle of Scotland. The chronicle does make good reading, and is ambitious in scope. It is often criticised as pseudo-history, and much of it is exaggerated fiction, but it might rely on materials that were once housed in the Monastery of Iona, now lost to time. If such materials did exist, they may well have referred to an ancient cultus to this individual.

Crathlinthus was a successor to a royal dynasty fraught with trouble. Within the narrative of Boece, his life is placed somewhere between the reigns of the Roman Emperors Florianus and Diocletian, placing it in the late 3rd century and early 4th century. He succeeded his brother, Donald, who had been killed fighting against another Donald - Donald of the Islands. The historical background to this warfare is quite interesting, as the Hebrides are consistently cast in opposition to the Christianised lands of Albion. This might take inspiration from the political circumstances of the 15th century, of which Boece would have been well aware, notably the conflict between the Lords of the Isles and the Scottish Crown. We might also perceive an echo of the tensions between Somerled and Malcolm IV, in the 12th century.

In any case, the Hebrides are characterised by Boece as a place of last refuge for criminal elements. It is to the Hebrides that king Athirco attempts to escape, without success. Athirco’s reign had been that of a despot, and after violating the daughters of one of his noblemen, there was rebellion. This nobleman was Natholoc, a man with no links to the previous dynasty, and who succeeded Athirco. Unfortunately, he was corrupt, and his reign proved to be a disaster. Amidst all of this, Athirco’s three sons are soon restored to the scene - one of them was Findoch, who ruled for some time, before being betrayed by his brother Carantius, allied with Donald of the Islands. The third of the brothers ruled as Donald III, whose reign lasted less than a year, and who we have already mentioned. Donald of the Islands became the king by usurpation, and it is in this context that we find the character of Crathlinthus introduced.

The son of Findoch, Crathlinthus conspires with a few others to assassinate Donald of the Islands, and to overturn his entire regime. This is met with great success, and is presented in the context of justice. What follows is an account in which he appears as the ideal ruler, almost in the pattern of one of the holy kings of the Old Testament. His initial methods are quite brutal, and we are told by Boece that he orders the extermination of all of Donald’s family, irrespective of their age or sex. While his first contacts with the neighbouring Picts are positive, civil unrest soon ensues without much pretext. Different factions of Picts and Scots fight against one another, without the support of their respective kings. Crathlinthus maintains the peace as far as he can, while also taking into account the realities of public opinion.

At this time, Crathlinthus’ uncle Carantius returns to the scene. He is received back with mercy, even if he had been guilty of the murder of Findoch, the king’s father. He helps bring the Picts and the Scots back into a working relationship, they are able to finally make peace, and to join forces against the Romans. Indeed, we might say that is the mercy of Crathlinthus which precipitates all of these events. Carantius gained the honour of becoming king of the Britons, after conquering the city of London. After a peaceful reign of seven years, he is killed by the Romans, and more conflict ensues. Boece tells us that Diocletian’s persecution of Christianity had an effect across Britain, and it is in this context that Coel succeeds Carantius. Like his predecessor, he was also opposed to Roman rule - he is likely the inspiration behind the rhyme “Old King Cole”, and he has some historical reality as Coel Hen. However, the narration becomes legendary, as we learn that Coel’s daughter was St. Helen, who married the Emperor Constantius, so that peace could finally be made with Britain. In other words, we are led to believe that the conversion of St. Constantine the Great and the discovery of the True Cross were contingent on the events narrated by the author! We are also led to believe that Christianity was present in Scotland from a very remote period, and we’ll come back to that soon.

Suffice it to say that in the context of these events, Crathlinthus defends Christianity, by receiving those who fled north from these persecutions against the Church. Boece tells us:

“King Crathlinthus gave these refugees a kindly reception, and allowed them to settle on the island of Mona, where he had caused a church to be built in the name of our Savior, having torn down its pagan temples and eradicated the Druids and their rites ... This was the first of all our Christian churches, as our writers have recorded, to be dedicated as a bishop’s see. It is now called the cathedral of Sodor, and the meaning of that name (as is true of the names of many other things and places) is lost in the mists of time.” (The History and Chronicles of Scotland, Book VI)

The mention of the Diocese of Sodor in this context is interesting, as its historical origin appears to have come from the Church of Norway, with most of its territories in the Hebrides! The Isle of Mona is clearly the Isle of Mann, which was the epicentre of this Diocese. In some sense, it seems that the conflict with the non-Christian Hebrides has now come full circle. Crathlinthus dies, according to Boece, in the year AD 322. The Crown then passes to his cousin, Fincormach. The key elements of his biography appear to be as follows: an almost miraculous restoration to the throne, with the associated meting out of justice, patient rule in adversity, and clemency that led to a lasting peace. Unlike many of the other characters in the chronicle, Crathlinthus has a natural death.

We noted that Boece’s work suggests that Christianity arrived in Britain at a very early date. This is confirmed by the second of the Saints we mentioned initially, St. Dovenald. King Donaldus I, or Dovenald, is presented as the first Scottish monarch to have embraced Christianity. In Book V of his chronicle, Boece writes about how Donaldus I sent ambassadors to Pope St. Victor in Rome. In response, the Pontiff sent on clergy to Scotland, so that Donaldus and his entire family were Baptised. This is supposed to have occurred in the late 2nd century. It is notable that Boece also mentions the reign of St. Lucius, king of the Britons, just prior to his writing on Donaldus. Tradition records that St. Lucius was the earliest Christian king in the British Isles, and that he wrote to the predecessor of St. Victor, Pope St. Eleutherius. Beyond these points, there is very little said about Donaldus, his role in the narrative is one of foundations, and his status as the first Christian king in Scotland suggests his Canonisation.

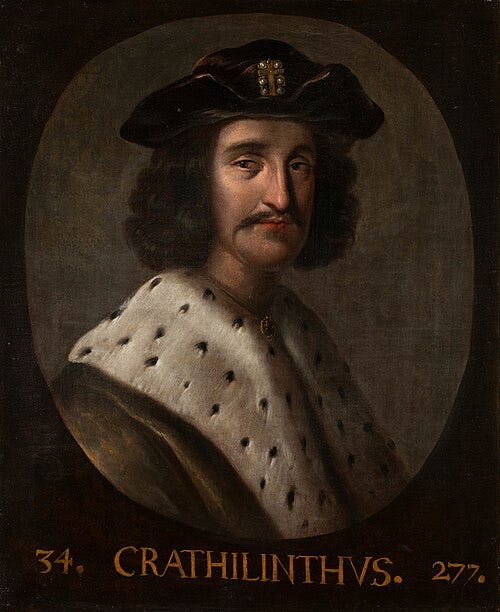

We haven’t explored any of the other names on the Dunkeld Litany, and much more work might be done to elucidate their relative hagiographies. Many of them may be just as obscure as the two Saints we’ve presented here, but others will have more substance. In any case, this brief glance at the Litany shows how little we are really able to say in regards to the Saints of the earliest periods of Scottish history, and how difficult it is to deal with legendary hagiographies. St. Dovenald and St. Crathlinthus inspired some of the efforts of the 17th and 18th centuries which sought to trace greater antiquity to Scottish history, almost in competition with other European countries. For this reason, we find imagined portraits of them, and these are attached to the article. If they had any historical reality, perhaps it was as ancient chieftains, somewhere in ancient Scotland. Perhaps all that we really have are their names. We know that Catholics probably invoked their intercession, while praying the Dunkeld Litany, and this means something.

By Anthony MacIsaac