When the Irish came to Scotland

Scots Catholics and their reaction to Irish immigration in the 19th Century. Part 1: Apostatis and Tratouris: 1560-1707

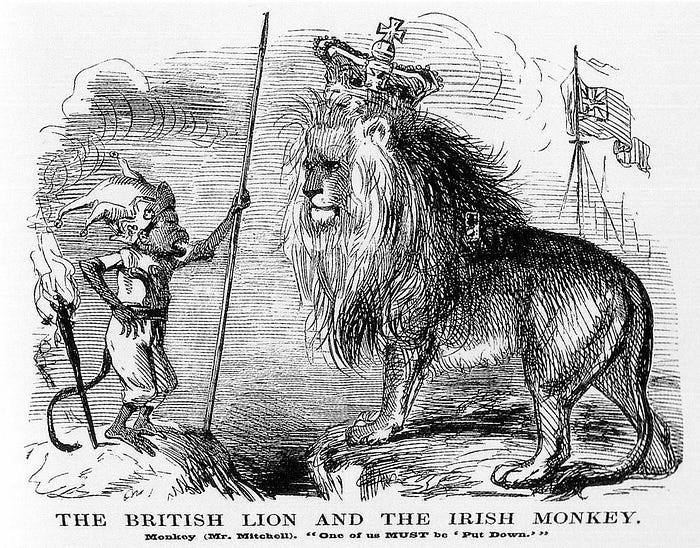

The British Lion and the Irish Monkey, Punch, 1. April 1848

The story of the Catholic Church in Scotland over the past 500 years is one of collapse, barest survival and slow emergence. Catholicism in Scotland is old, however the institutions and personality of the Church we see today was formed in the 19th Century; and no story about the Church could be told without talking about Irish immigration to western Scotland; beginning in the late 18th Century, reaching a chaotic crescendo in the 1840’s and 50’s and was an ever present feature of Scottish life throughout the 19th and into the 20th centuries. When we look at Glasgow, Paisley, Motherwell as well as Ayrshire and indeed Dundee we are seeing a Scotland – and a Church, literally built on the backs of these often desperate men and women from across Ireland.

In this three part series: I want to look at what happened when the Irish came to Scotland from the end of the 18th century up to the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1878. We will explore the response of both the Scottish Catholics, and indeed the Protestant majority – both of whom, and for their own reasons revealed deep prejudices and fears about their arrival and look in more depth at the reactions of the Catholic hierarchy of the time. However to do this we will first go back a little to put it in context.

Part 1: Apostatis and Tratouris: 1560-1707

For Scottish Catholicism the reformation was a disaster, and would struggle for survival until the 19th century. This struggle would help inform their own attitudes to Irish Catholicism and the Union itself. In the early reformation period, as the Catholic church dissolved, when even as early as 1562 the Papal Nuncio sent to Queen Mary Stuart would report on the dearth of Priests and the secrecy which Mass had now to be said. The Kirk, which saw itself as the national embodiment of Scotland, and whose powers of excommunication could include a ban on trade, employment and holding public office – could be laid upon anyone living in Scotland, but especially to Catholics - was the force used to bring conformity to Scottish religious life. A later example of this was the apprentice bakers of Perth in the mid-17th Century who so stirred the ire of the local Kirk with their revelry connected with Saint Obert ; they found themselves banned from trading in the city itself. In this atmosphere Fr William Murdoch SJ, without any hierarchical say so would tell those he served that it was a necessity to conform to the new Protestant faith outwardly whilst remaining interiorly Catholic. In this period many of the wealthy families like the Gordons of Huntly or Hegates of Glasgow could stay true to Catholicism and yet appear to conform to the Kirk. Not all would be so subtle, and although we know little of ordinary Catholics and how they navigated the Kirk, we do know, and some of this from Kirk Ministers frustrated letters, that many would feign conformity, make excuses for not being present at communion and learned to play the system.

Although Catholicism would survive, it receded to the periphery with the majority (certainly in lowland areas) converting to Protestantism. Along with the generally negative legal and spiritual atmosphere, for many decades of the 17th century there was no official Catholic presence in Scotland. Missionary Priests, many of whom were Scots would come and go, being resident in other countries. Many also became private chaplains of rich families on continental Europe which exasperated the problem of priestly numbers. There was also often more Priests in lowland areas than would venture to the north. Irish Franciscans and other ‘freelance’ missionary Priests from Ireland would be the lifeline for many of the isolated Gaelic communities but over the course of the 17th century they were beginning to be seen as more of a problem by Scottish clergy than a blessing. Accusations of improper behaviour masked national rivalries. The result would be, as one scholar noted, by the 18th century, Scottish Catholic Bishops would harden themselves against Irish Priests which was to remain to be the case until the late 19th century.

For the Kirk, as Knox had loudly proclaimed, Catholics were ‘Apostatis and Tratouris’ (apostates and traitors), and although this was part of a tract he wrote concerning doctrine, this could also be applied politically. Any allegiance to the old faith was detrimental to the prosperity of Scotland before God, and as we shall see, a lot of legislative effort went into to stamping it out. This would lead to an outward conformity amongst those who remained in the faith resulting in an interiorising of Catholicism which would leave a powerful, still present, foothold in the minds of her adherents. As R.S Spurlock wrote:

‘As such Catholicism did not need to be contested at the national level to be authenticated, rather it was embodied in loosely connected networks, private households or in personal piety. For the Maxwells and Huntlys, their continued support for the old faith within the bounds of their traditional hegemonies strengthened their influence, which in turn solidified their regional dominance. Moreover, the rejection of a national obligation opened the way for the faith to be authentically privatized and this gave Catholicism and its adherents resilience’.

This more conformist attitude is detectable in the 18th and 19th century Scottish Bishops who were drawn primarily from the recusant families of the north east and would play out when faced with the needs of Irish Catholics. In an illuminating observation, by the 19th century, Scots Catholics were thought closer akin to their Protestant neighbours than to the sort of Catholicism the Irish immigrants knew. Part of the reason for this was that the reformation in Scotland was almost total in its success reducing Scottish Catholics to a mere 6000 in 1650 (although that would almost triple a century later); for the Irish however, the reformation did not succeed and most would remain attached to their faith but dominated politically by a Protestant minority. The politics of these two opposites would play out in the 19th century and would cause tensions between the Scots Bishops and their Irish flock.

Scottish parliaments, councils and the Kirk enacted Penal laws over the course of the 16th and 17th centuries trying to root out Catholics when they could, at times this might be relaxed, or strengthened, which often had to do with national politics as much as the theological. Penal laws included prohibitions on buying land, entering professions, voting, holding public office, mass attendance and of course hosting any Priests.

Respite would appear though in the renewed monarchy of Charles II and his ascension to the throne of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1660; however the Scottish Parliament in 1661 would pass an Act ‘against Papists and Priests’, which was necessitated ostensibly by the ‘increase of Popery, and the number of Jesuits, priests and Papists which have of late and do now abound in this kingdom in far greater numbers than ever they did’. The Act ordered the removal of all Clergy from the land and lists made of suspected or proved lay Catholics. Catholic children would be removed to protestant education as well. Another Act passed in 1670 would ban Catholics holding high office, and barring a brief interregnum when Charles II removed the Penal laws - they were back after a strong reaction from Protestants - as can be seen in the 1673 Scottish Privy Council order (once again) banning clergy, Mass and the sacraments. By 1681 the atmosphere was febrile with talk of ‘Popish Plots’ that would see Scottish Acts that would defend the Protestant faith through ratifying all previous penal laws and lists of all lay Catholics to be made in each parish. Again though, at the ascent of James VII & II to the throne a relaxation of all Penal laws and protection to all Clergy was rolled out in 1685 ratifying it by his ‘Sovereign Authority, Prerogative Royal, and Absolute Power’ which did not go down well at all.

This precipitated the so-called Glorious revolution in 1688-89 bringing the Protestant William of Orange, and Mary, daughter of James VII to the throne in a bloodless coup. The mix of sectarianism, fear of absolute monarchy and of foreign invasion from France and Spain - along with the vibrant Catholic Counter-Reformation in Europe would end the Stuart dynasty as Sovereigns. This would further underline the doubts surrounding Catholic loyalty to the State, which Jacobitism would further fuel. The Stuarts did have many loyal Catholics in its ranks, but it should be noted that Episcopalians were the more numerous Jacobites and would face heavy persecution for it. By the late 17th Century a 1693 Act would see the disarmament of all Catholics (and non-jurors - Episcopalians) who did not take the oath of allegiance which would be further strengthened by 1700 with no Catholic being able to teach, hold professions, buy or inherit land or leave as legacy any monies to Catholic organisations.

Enforcing the various Acts at suppressing Catholicism (and indeed Episcopalians) was however a different matter and was, at times quite difficult for local Magistrates to achieve - or often, even want to. It seems the case that if you could achieve an outward appearance of Protestant faith, as mentioned above, and go about your life quietly, you could avoid the worst of it. Certainly, Catholicism and Priestly numbers did grow in the 17th century which shows that for all the rhetoric of the Parliaments; suppression rather than destruction was the path the authorities took.

This can be evidenced by some of the continuing customs found by writers travelling throughout the highlands in the early 18th century. One noted the veneration of St Barr on Barra:

‘The natives have St. Barr’s wooden image standing on the altar, covered with linen in form of a shirt; all their greatest asseverations are by this saint. I came very early in the morning with an intention to see this image, but was disappointed; for the natives prevented me by carrying it away, lest I might take occasion to ridicule their superstition, as some Protestants have done formerly; and when I was gone it was again exposed on the altar’.

In other places veneration of Saints for healing and on their appointed days would still continue and to many non-Catholics it would appear as superstition and magic. But within the context of almost no institutional Church and few opportunities for the sacraments it is remarkable anything did survive at all. Certainly the difficult terrain of the Highlands and Aberdeenshire helped protect them. But what this did produce was a more interior faith that was bolstered by community and would lend a resilience to those who remained Catholic.

However as the 18th century would dawn, new opportunities afforded in that century after the 1707 Act of Union would begin to trickle down to ordinary Scots; the recusant Catholics were not willing to remain in the shadows and desired to stake a claim in the new Scotland and indeed the new Britain that would be born. This period between the mid 16th and early 18th centuries, with its pyretic anti-Catholicism was often coupled with fears of external threat and internal strife. A virulent national identity that linked Protestantism with a constitutional monarchy and parliament seemed at odds with their perception of Catholics and Catholicism more generally. It was this perception that many Catholics would work hard at dispelling as we go into the 18th and 19th centuries, but in the 19th century in particular, the Catholicism of the incoming Irish, and its linkage with Irish nationalism would pose a threat to the ambitions of Scots Catholics and indeed their Bishops.

By Eric Hanna, Editor.